Arts

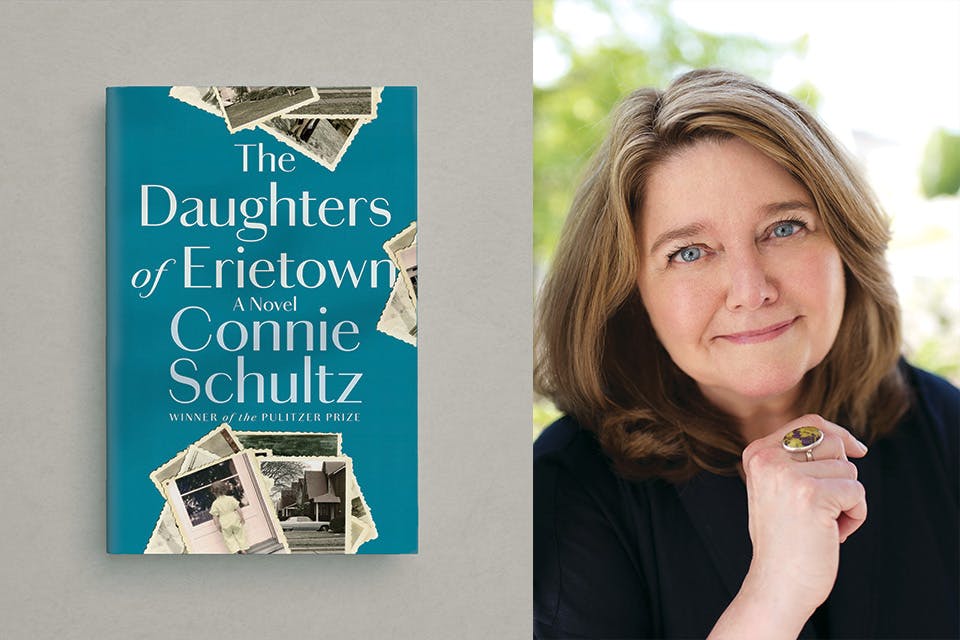

Connie Schultz on ‘The Daughters of Erietown’

The author and Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist’s debut novel delves into the dreams and realities of working-class families.

Related Articles

Follow-Up With ’True Raiders‘ Author Brad Ricca

The Cleveland-based author’s new book delves into the details behind a real-life 1909 expedition to find the Ark of the Covenant. READ MORE >>

Ohio Literary Trail

This book lover’s road trip includes the family home of the woman who helped change Americans’ views on slavery and a museum celebrating the art of the picture book. READ MORE >>

Eliese Goldbach on Writing ‘Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit.’

The author spent three years working at Cleveland’s ArcelorMittal plant, which she recounts in her debut book. READ MORE >>