The Crash of the USS Shenandoah

In September 1925, the U.S. Navy’s heralded flying machine crashed in Noble County, killing 14 crew members and becoming forever tied to this corner of Ohio.

September 2018

BY Jim Vickers | U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph

September 2018

BY Jim Vickers | U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph

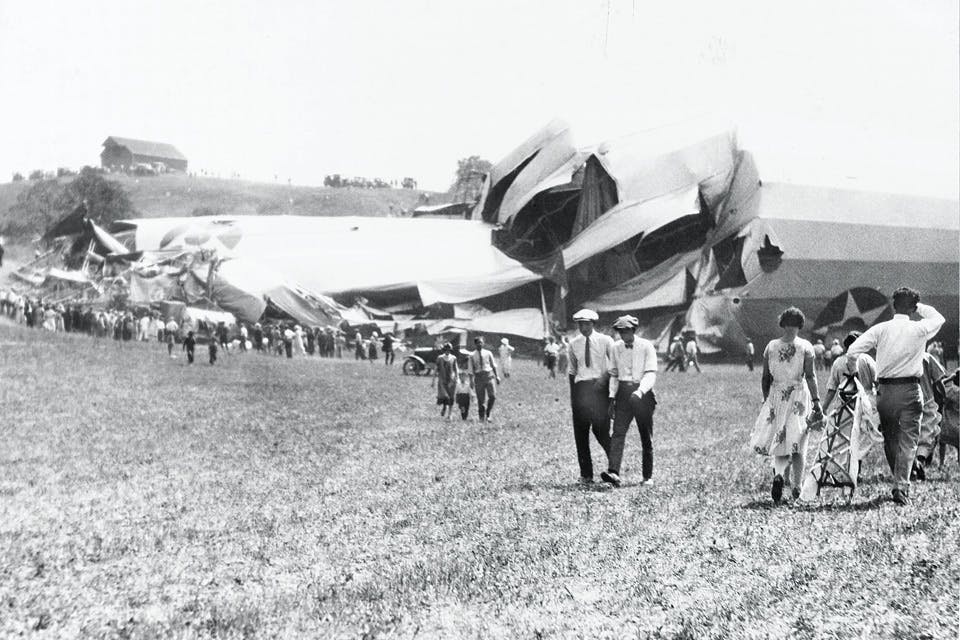

The crowds began arriving at first light. On foot and by automobile, they traversed the narrow dirt road that stretched a mile and a half from the Noble County village of Ava to a monstrous and mangled section of the USS Shenandoah. An Associated Press report noted the reddish dust covering the road was four inches deep in places, requiring drivers to stop and wait for particles kicked up in the air to clear before continuing forward. The slowdowns only led to further traffic congestion.

Those headed to Charles Neiswonger’s southeast Ohio farm the morning of Sept. 4, 1925 , were drawn by the tragic demise of the U.S. Navy’s iconic, 680-foot-long airship. Twenty-four hours earlier, a terrible storm had destroyed America’s first rigid, helium-filled dirigible, killing 14 of its 43 crew members. The Shenandoah had been passing over Ohio as part of an 11-state tour of the nation. But during the early morning hours of Sept. 3, 1925, it hit a line squall — a string of storms that the AP report described as “most feared by airmen.”

There was no instant moment of disaster, but rather a violent wrenching that lifted the airship into the heavens and twisted it past its breaking point, ripping it into pieces and scattering it across Noble County. Among the victims was the ship’s commander, Zachary Lansdowne of Greenville. As morning light broke across the countryside, the ruined ship lay shattered, along with the optimism that the Shenandoah had instilled in the American public during the two years since its unveiling.

“And for the citizens of Noble County, Ohio, it was as if visitors from the future had come tumbling out of the skies and into their lives,” author Jerry Copas wrote in the introduction to his 2017 book, The Wreck of the Naval Airship USS Shenandoah. “The wondrous vessel christened ‘Daughter of the Stars’ would forever leave its imprint on their quiet, peaceful community.”

The looting began almost immediately, with locals swarming the main section of the craft to take home a bit of history. A photograph printed in Washington D.C.’s afternoon newspaper, The Evening Star, four days after the wreck shows three men — one dressed in suit, tie and hat — holding pieces of the craft that were taller than they were. But that represented a mere fraction of the souvenir hunters who made their way to Neiswonger’s farm in the wake of the tragedy. Eventually, soldiers from Fort Hayes in Columbus stopped the looting by keeping crowds 100 feet from the wreckage, but the damage was done.

“Covering and cells had all been torn away with the exception of some of the silver cloth over the uppermost part of the ship’s remnant,” an AP report noted. “Cables, platforms, joints, gasoline tanks, electric communication wires — everything detachable was gone.”

***

Exactly eight months before the Shenandoah was last seen 4 miles outside Wheeling, West Virginia, “heading due west showing three lights,” The Evening Star ran a headline in its Jan. 3, 1925, edition proclaiming “Dirigibles Easily Ride Worst Gales,” followed by “Officer from Shenandoah Says ‘Runaway’ Flight Proved This.”

The Jan. 3 report appeared following U.S. Navy Lt. J.B. Anderson’s address to the American Meteorological Society as part of sessions held by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Other fields of research discussed during the event included the effect of light on living things and the temperatures and atmospheric conditions of the planets. “Observations that chimpanzees can really think attracted much attention,” the article noted.

Anderson’s argument was a solid one at the time, given what he had seen as crew meteorologist of the Shenandoah the previous winter, when high winds ripped the great ship away from its mooring mast at Lakehurst, New Jersey, where the dirigible was based. Anderson, who had not been aboard at the time, recounted his role in the effort to locate the ship.

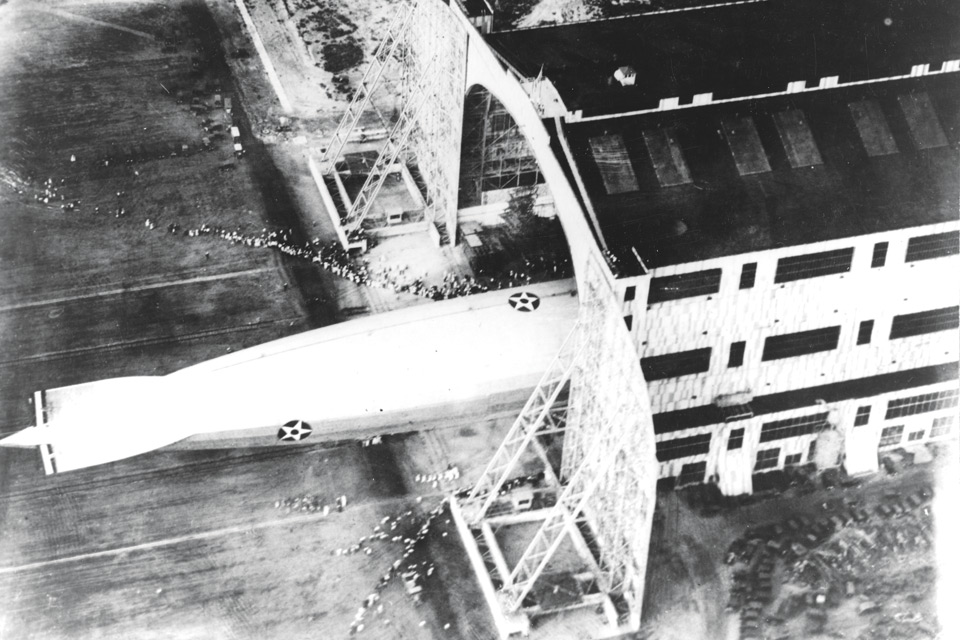

USS Shenandoah leaving the airship hangar at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey. Probably photographed when the airship left the hangar for the first time, on Sept. 4, 1923. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph)

“We raced for the woods in automobiles, but found no trace of the Shenandoah. A farmer then told us he had heard her engines a few minutes before,” Anderson said. “That meant that her crew was so efficient that before a 90-mile gale had swept her four miles, the engineers had the engines going, and I no longer had any fear as to her safety.”

The report gave those who hoped to expand the United States’ dirigible program a sense of security. Three days after the article detailing Anderson’s conclusion, another article in the newspaper heralded a “busy six months had been mapped out by the Navy Department” regarding the Shenandoah and the Los Angeles, the Navy’s other dirigible, but one permitted only to be used for commercial purposes. The Shenandoah was made for military action, its design influenced by an earlier German airship, Zeppelin bomber L-49, that French forces captured nearly undamaged in October 1917.

But before it was to defend the nation, the Shenandoah had to first conduct a mission of promotion. As Copas details in his book, an October 1924 publicity tour saw the airship embark on a 19-city trip across the United States that took it from Lakehurst, New Jersey, to San Diego before traveling north to Seattle and then returning to Lakehurst. It was a rousing success.

“Requests poured in from cities and towns who wanted to see the ‘Daughter of the Stars’ in the skies over their communities,” Copas wrote, “and the Navy was eager to accommodate.”

***

The trouble started just before 5 a.m. during the early morning hours of Sept. 3, 1925. The Shenandoah was at 3,000 feet, heading west on a course that was to take it over Columbus and Indianapolis before landing and refueling at Scott Field in Missouri. The airship was then to continue on, passing over St. Joseph, Missouri; Des Moines, Iowa; Eau Claire, Wisconsin; Fond du Lac, Wisconsin; Milwaukee; Minneapolis/St. Paul and Detroit. Upon reaching Detroit, the Shenandoah was to be tied up at a new mooring mast built by Henry Ford.

The 11-state tour was to wrap up in six days, but not before chief petty officer France Master parachute jumped from the airship over Akron, “where he was to ‘drop in’ on his wife and newly born son,” the AP noted in its coverage of the wreck.

Col. C.G. Hall, a United States Army observer who had been in the control cabin of the Shenandoah up until moments before its destruction, told reporters the airship had changed course “a dozen times” to avoid the storm it was flying into, only to encounter the line squall, which catapulted the flying machine to an altitude of 6,000 feet.

“We opened the valves to let out gas and lowered the ship and were drawing away from the storm at a 50-mile-per-hour rate, when the storm enveloped us and broke the ship into three pieces,” Hall recalled. “When the crash came I was on the ladder leading from the control cabin to the rear portion of the ship. As I started to fall I clutched a girder, to which I hung suspended, finally swinging my body over it and crawling 40 or 50 feet back into the ship.”

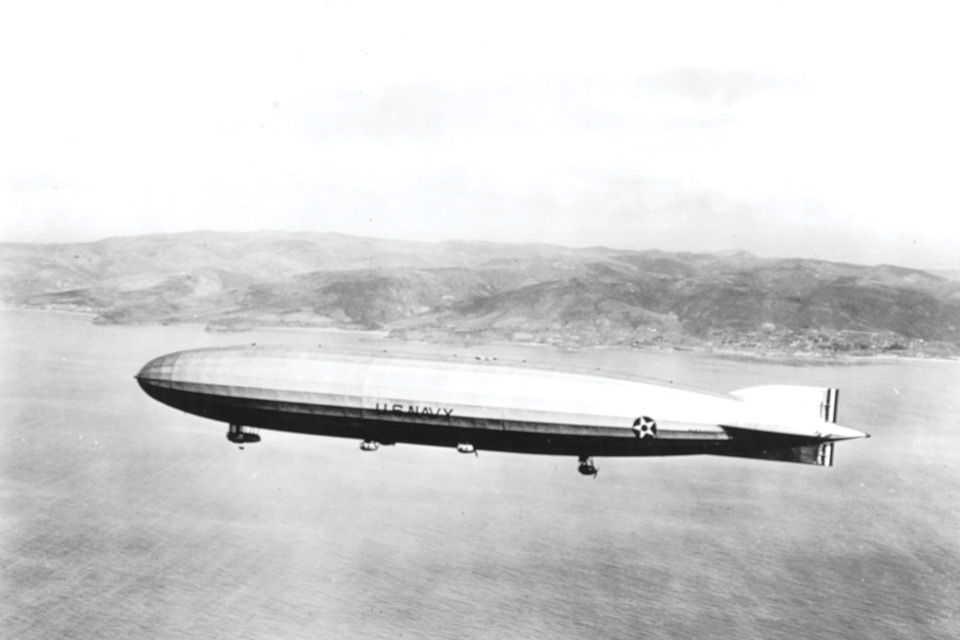

USS Shenandoah in flight, circa 1924. This official U.S. Navy Photograph is now in the collections of the National Archives. (Naval Historical Foundation, U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph)

Eight men, including Hall and J.B. Anderson (whom eight months earlier had proclaimed the ability of dirigibles to survive the highest winds), rode the front portion of the ship through the air for a half hour and more than 12 miles before landing safely, thanks to crew members who navigated it like a giant balloon. A 450-foot section of the ship landed 1 1/2 miles from the village of Ava, and the control cabin was found nearby.

In the hours after the crash, reporters interviewing residents of Noble County encountered two families who had witnessed the Shenandoah’s demise.

“In the weird half light of the early morning storm, with angry clouds hanging in the heavens, rent intermittently by forks of lightning, the families of S.O. Davis and Frank Nelson, farmers living near Ava, watched the death struggle between the elements and the giant dirigible,” the Associated Press reported on Sept. 3, 1925. “They saw the Shenandoah stand motionless in the air for 15 minutes. They saw her dart upward under the terrific air pressure: saw her buffeted and tossed, first in one direction and then another, finally to be torn to pieces by the angry demons of the air.

***

By the evening of Sept. 4, 1925, Charles Neiswonger was beginning to have second thoughts about charging an admission price to see the main portion of the wreckage on his property: 25 cents per person or $1 per car. By the time he hit $500, Neiswonger was concerned the federal authorities on scene would arrest him.

“Frightened at what he thought was a penitentiary offense, he disappeared and was not heard from until early last evening, when he came to town to consult his friend, Sheriff Shafer,” detailed the AP’s report.

“The sheriff informed him that his ‘business’ was legal, and that the only opposition he had heard was from neighbor farmers, who objected to the ‘hold up,’ ” the article noted. To combat the criticism, Neiswonger announced a rate of 10 cents per person and 50 cents per automobile, effective at sunup Sept. 5.

As the hours turned into days, vital pieces from the crash that could help investigators determine what happened began to turn up. The baragraph, which could help glean the Shenandoah’s altitude during the storm, was located in Cambridge, while the airship’s log sheets were in the possession of a local souvenir hunter.

The wrecked airship's after section, taken soon after it crashed in southeast Ohio. This view shows the starboard forward part of the after section, with Shenandoah's top national star marking in left center and one of her five engine cars in the right foreground. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph)

But many parts of the Shenandoah weren’t found until years or even decades later — kept as family heirlooms passed down over the generations.

By Sept. 9, 1925, it was announced the Aluminum Co. of America was the highest bidder for the junking of the wrecked airship. The Pittsburgh-based company bid 20 cents per pound to remove the roughly 50,000 pounds of wreckage in order to harvest the aluminum, copper and manganese used to build the dirigible.

On the same day, the Justice Department issued orders to prosecute those who had taken important sections of the Shenandoah as souvenirs. Even today, close to a century later, parts of the famous airship are still out there. As recent as June 2018, the television show “Pawn Stars” featured a package of items from the USS Shenandoah that included a piece of the wreckage itself, a copy of the Daily Jeffersonian newspaper from Sept. 4, 1925, and an inflatable promotional mini zeppelin. The trio of items went for $750.

In 1937, the federal government erected a bronze and stone monument to the Shenandoah in Ava. In 1975, on the 50th anniversary of the crash, the people of Noble County added two more markers, one where the control car of the airship had ended up and one where the nose section of the Shenandoah landed safely.

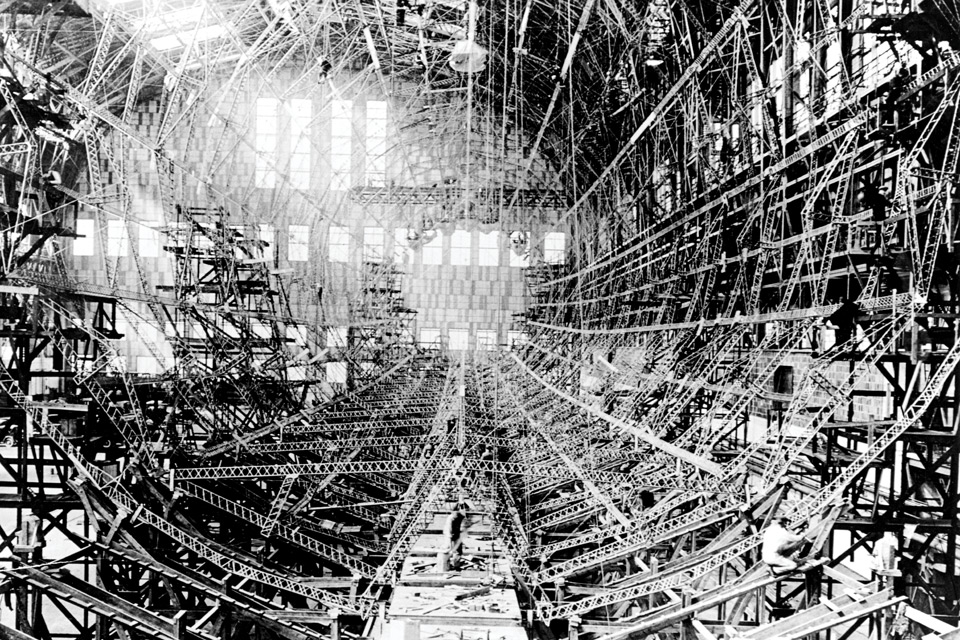

View of the USS Shenandoah interior, while it was under construction inside the airship hangar at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1922-1923. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph)

The late Brian Rayner, who grew up on the Neiswonger farm property and maintained the Shenandoah crash site for decades, assembled a one-of-a-kind mobile museum of photographs, newspaper clippings and other artifacts tied to the famous airship. Following his death in 2013, his widow, Theresa Rayner, now oversees the collection.

Those who want to pay tribute at the 1937 Shenandoah monument will today find it relocated to a spot along State Route 821 on the north side of Ava. Look closely, and you’ll see a bronze depiction of the airship, being surrounded by swirling plumes of clouds as it hangs several feet above a placard naming all 14 men who perished.

The rest stop along Interstate 77 near mile marker 40 is home to an Ohio Historical Marker that reminds travelers of what happened in this corner of the state and how it reshaped American policy regarding dirigibles, starting off with the words: “Wind increasing in volume. Get no chance to …”

“These were the last words from the doomed Navy airship Shenandoah, caught in a violent storm crashing 7 miles northwest of this spot near Ava at dawn September 3, 1925,” the text on the marker explains. “While souvenir hunters stripped the wreckage, a nation questioned the value of huge, rigid dirigibles … Smaller blimps replaced the dirigible as America’s lighter-than-air sentinels of the sky.”

Related Articles

.jpg?sfvrsn=21d9b438_3&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Discover 3 Newly Recognized Underground Railroad Sites in Appalachian Ohio

The National Park Service has recently acknowledged three Ohio communities that played a role in helping Civil War-era freedom seekers. READ MORE >>

Learn the Sweet History of The Dawes Arboretum at Maple Syrup Day

The Newark arboretum’s founders, Beman and Bertie Dawes, began harvesting sap for maple sugar in 1919. Today, the annual Maple Syrup Day shares that heritage with visitors. READ MORE >>

New Book Details Origins and Evolution of Dayton’s Carillon Historical Park

The destination’s vice president of museum operations Alex Heckman and curator Steve Lucht wrote the 222-page, hardbound coffee-table book. READ MORE >>