How Ohio’s Canal Era Helped Shape the State’s History

A groundbreaking idea began to take shape in Ohio 200 years ago this summer, as the simultaneous creation of two major canals ultimately opened the state to trade and transformed the place we call home.

July/August 2025

BY Damaine Vonada | Photo courtesy of Ohio History Connection

July/August 2025

BY Damaine Vonada | Photo courtesy of Ohio History Connection

In 1824, Stephen Frazee was a subsistence farmer who had one cow and likely lived in a log cabin along the Cleveland stagecoach route. By December 1827, he owned eight cows, was shipping milk and dairy products on the Ohio & Erie Canal and had moved his family into a new, two-story brick house facing the waterway.

“Anywhere the canal went, prosperity flowed,” says Rebecca Jones Macko, an interpretive park ranger at Cuyahoga Valley National Park, where the Frazee House still stands today along a stretch of the aptly named Canal Road. The home is on the National Register of Historic Places and serves as a silent but steadfast testament to the canals’ impact in transforming Ohio from an undeveloped, economically isolated frontier state to a wealthy, influential and important part of the nation’s agricultural and industrial lifeblood.

Ohio’s canal era began on July 4, 1825, as Ohio Gov. Jeremiah Morrow and New York Gov. DeWitt Clinton, who had spearheaded his state’s thriving Erie Canal, met near Newark. As cheering crowds watched, they dug shovelfuls of earth to mark the start of work on the Ohio & Erie Canal, which would connect Portsmouth on the Ohio River to Cleveland on Lake Erie. The men met again in Middletown on July 21, 1825, and to similar fanfare, broke ground for the Miami & Erie Canal, another Ohio River-to-Lake Erie route that eventually extended from Cincinnati to Toledo.

The completed sections of Clinton’s “Big Ditch” between the Hudson River and Lake Erie had boosted New York’s economy by slashing transportation costs, and Ohioans had high hopes that canals would do the same for their state. Though rich in land, Ohio was cash poor. In 1820, barely 600,000 people lived in Ohio, and most were threadbare farmers struggling to get products from their backwoods farms to lucrative markets. Sending wagons across the Appalachians to eastern cities was expensive, time consuming and risky, and so was putting surplus crops on flatboats floating south to New Orleans.

Since the state’s financial survival depended on inexpensive and efficient transportation, Ohio legislators followed New York’s example of a canal system owned and operated by the state. Whereas New York had constructed one canal, Ohio leaders decided to simultaneously build two canals at an estimated cost of $6 million. Their plan was to fund construction by selling bonds, then repaying the debt with revenue from tolls and selling water for power.

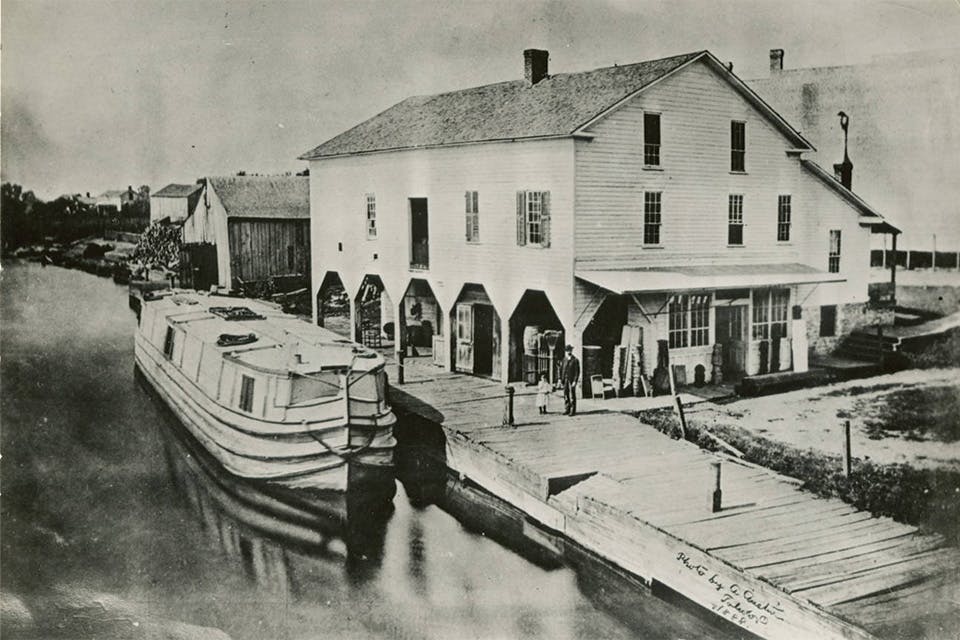

The Buckeye State’s canal era began on July 4, 1825. The Ohio & Erie Canal put Akron on the map. (photo courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, University Libraries)

The canals were an ambitious undertaking for a raw and relatively young state. It had only been 30 years since the Treaty of Greenville halted the Northwest Indian Wars and opened Ohio to white settlement; only 22 years since Ohio achieved statehood; and only 10 years since the end of the War of 1812 ensured permanent peace in the Buckeye State. Ohioans, however, were in a hurry to dive into the mainstream of American commerce.

“People didn’t ask, ‘Can we get a canal done?’ Instead, they asked, ‘How fast can we get it done?’” says Andy Hite, a Canal Society of Ohio vice-president and self-described “gongoozler” (person interested in canals and canal life). By November 1825, thousands of men were at work carving two waterways into Ohio’s landscape.

The canals employed local farmers, skilled engineers and tradesmen from New York, but Irish and German immigrants did most of the manual labor on the canals with picks, shovels and wheelbarrows. Their task was backbreaking, and the initial pay for toiling from sunrise to sunset was 30 cents a day. Often working in mud and waist-high water, the workers lived in shanties and received daily rations of whiskey to ward off the dreaded chills and fevers of ague.

“There was a saying that for every mile of canal they dug, an Irishman died,” Hite says.

The minimum canal dimensions were 40 feet wide at the top,

26 feet wide at the bottom and 4 feet deep. A 10-foot-wide strip of land parallel to the canals — the towpath — had to be cleared for the mules and horses that pulled canalboats,

and locks were built to compensate for changes in elevation. Because canalboats were usually 79 to 89 feet long and 13 to 14 feet wide, lock chambers measured at least 90 feet long and 15 feet wide, and their stone-lined walls had wooden gates at

both ends. After a boat entered a lock, it could be raised uphill by closing the gates and filling the lock with water or, conversely, lowered downhill by opening the gates and letting water run out.

Water poured through the gates of the locks on the Ohio & Erie Canal near Zoar. This photo has been dated to the late 1800s or early 1900s. (photo courtesy of Ohio History Connection)

Just two years after work on the Ohio & Erie Canal began, its first section opened on July 4, 1827, when the bunting-draped State of Ohio canalboat departed Akron on a 38-mile trip to Cleveland. Akron existed solely because of the canal. Gen. Simon Perkins, a surveyor and War of 1812 veteran, not only co-founded Akron in 1825 but also donated land in the middle of it for the canal right-of-way. Akron, which comes from the Greek word àkros, meaning “summit” or “high place,” sits on a summit that is 395 feet higher than Lake Erie, and thus, to reach Cleveland for a gala Fourth of July celebration, the State of Ohio had to descend through 44 newly built locks.

By 1845, Ohio boasted a sprawling and complex system of canals. It consisted of slightly more than 1,000 miles of main and branch canals, 294 lift locks, 29 river dams, 44 aqueducts and 33,000 acres of reservoir surface area, which included the then-largest manmade lake in the world — Grand Lake — on the Miami & Erie Canal.

“The total cost of the canals was about $16 million,” Hite says. “In today’s money, that’s more than $700 billion.”

Ohio’s canals were one of the preeminent civil engineering feats of the early 1800s. Carrying both cargo and passengers, they did exactly what they were intended to do: trigger rapid economic growth by opening markets and attracting new people.

The cost of shipping goods to the East Coast plummeted from $125 per ton by horse and wagon to $25 per ton by canal. Crossing the state from river to lake dropped from a few weeks to a few days. By 1850, Ohio had nearly

2 million residents and

was the third-most-populous state.

“The canals changed everything,” Jones Macko says. “They changed what people wore, what they ate, what they did for a living, how they perceived other cultures and the way they engaged with the world at large.”

Foods that were formerly considered luxuries, like coffee, sugar and spices, were made available by canalboats. They also hastened the demise of open-hearth cooking by delivering wood-burning stoves, as well as pots and pans. News traveled faster than ever before on the boats, and businessmen like Moses Gleeson, whose tavern now houses Cuyahoga Valley National Park’s Canal Exploration Center, subscribed to out-of-state newspapers so that customers could read them. Retailers transitioned from general stores to specialty shops because people were able to get cotton readily, so they didn’t have to create textiles (like linen) from scratch.

Canals fostered lumbering and mining, and cities like Akron mushroomed into manufacturing hubs as water discharged from locks helped power the city’s mills, foundries and machine shops.

Mile marker 181 of the Miami & Erie Canal was located behind the Dayton Fairgrounds. (photo courtesy of the Toledo Lucas County Public Library)

The canals also had unexpected and wide-ranging consequences. The German Separatists in Zoar paid off the mortgage on their land with wages they earned digging the Ohio & Erie Canal. A fatherless teenager named James Garfield got a job as a “hoggee,” who guided mules on towpaths. After he fell into the canal and contracted malaria, his mother persuaded him to return to school. Three decades later, Garfield was President of the United States.

When a 3-mile-long branch canal from Milan to the Huron River made the inland town a world-class wheat shipping port, Samuel Edison moved to the village, started a shingle-making business and built a brick house near the canal where his son Thomas was born in 1847. That house is now the Thomas Edison Birthplace Museum and tells the story of Edison inventions, like the incandescent lightbulb, phonograph and motion picture camera, that shaped the modern world.

Because the Miami & Erie Canal promised to make Toledo a trade center, the state of Ohio and territory of Michigan engaged in a dispute over land called the Toledo Strip. Both deployed militias and shots were fired, but the largely bloodless “Toledo War” ended with a compromise in 1836. Ohio got the Toledo Strip, while Michigan received statehood and its Upper Peninsula. On the Miami & Erie’s opposite end, Cincinnati’s German immigrants called the canal “the Rhine” and where they lived “Over the Rhine.” The nickname endured, and Over-the-Rhine is now a trendy Cincinnati neighborhood.

The canals’ heyday only lasted about 20 years because in the 1850s, they began losing money due to maintenance and repair costs. Railroads, which were faster and more reliable, were also expanding. By 1860, Ohio led the nation in railroad track mileage, and after the state’s disastrous 1861 decision to privatize the canals, the deteriorating waterways gradually shut down. But the sound of rain drops rather than train whistles was their death knell. In March 1913, downpours caused widespread flooding that destroyed canal ditches and locks.

Though their days as vital transportation corridors are long gone, canals laid the foundation for modern Ohio. Many communities, such as Canal Winchester, Chillicothe, Dover, Kent, Miamisburg and Troy, sprouted up around canals, and because those erstwhile waterways were turned into roadways, such as Cincinnati’s Central Parkway, Dayton’s Patterson Boulevard and Toledo’s Anthony Wayne Trail, canals still define cities. Canal streets abound in small towns, old towpaths serve as recreational trails and former canal reservoirs like Grand Lake St. Marys have become state parks.

The Milan Canal was started in 1833. (photo courtesy of Ohio History Connection)

Remnants of locks haunt Ohio like archaeological ruins. The Lockington Locks’ massive limestone blocks are an American Stonehenge, marking the Miami & Erie Canal’s high point and display distinctive grooves worn by the ropes of forgotten canalboats. In Groveport, the remains of Lock 22 anchor Blacklick Park, while Akron’s Cascade Locks Park showcases the Mustill Store at Lock 15, as well as the millrace where Quaker Oats founder Ferdinand Schumacher made cereal. And just outside Cuyahoga Valley National Park’s Canal Exploration Center, living history interpreters periodically show visitors how Lock 38 worked. It is the last original Ohio & Erie lock still functioning.

Born on a canalboat in 1872, Captain Pearl Nye lived and worked on the Ohio & Erie Canal until 1913. He wrote and recorded many folk songs romanticizing “those balmy days upon the old canal” that are preserved by the Library of Congress. Thanks to Ohio’s rich canal heritage, four historic canal stops conjure those days for modern visitors by offering narrated, mule-drawn and horse-drawn rides on reproduction canalboats.

On the Ohio & Erie Canal, the horse-drawn St. Helena III departs from Canal Fulton’s Canalway Center and travels to Lock 4, while just outside Historic Roscoe Village, where Nye built a house on an abandoned lock using old canalboat materials, the Monticello III is based at Coshocton Lake Park.

Near Piqua, the Johnston Farm & Indian Agency gives rides on the General Harrison and guided tours of the farmhouse where Miami & Erie Canal commissioner John Johnston and his family lived. And at Providence Metropark near Grand Rapids, travelers can sample Miami & Erie Canal life circa 1876 by riding The Volunteer through Lock 44 and touring the Isaac Ludwig Mill.

“This is the only place in the United States,” says Providence canal experience coordinator Jodie McFarland, “where you can ride a mule-drawn canalboat through an original canal lock and see an operating 19th- century water-powered mill.”

To learn more about Ohio’s canal era, visit ohiohistory.org/ohiocanals or canalsocietyohio.org.

For more Ohio history, sign up for our Ohio Magazine newsletters.

Ohio Magazine is available in a beautifully designed print issue that is published 7 times a year, along with Spring-Summer and Fall-Winter editions of LongWeekends magazine. Subscribe to Ohio Magazine and stay connected to beauty, adventure and fun across our state.

Related Articles

.jpg?sfvrsn=21d9b438_3&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Discover 3 Newly Recognized Underground Railroad Sites in Appalachian Ohio

The National Park Service has recently acknowledged three Ohio communities that played a role in helping Civil War-era freedom seekers. READ MORE >>

Learn the Sweet History of The Dawes Arboretum at Maple Syrup Day

The Newark arboretum’s founders, Beman and Bertie Dawes, began harvesting sap for maple sugar in 1919. Today, the annual Maple Syrup Day shares that heritage with visitors. READ MORE >>

New Book Details Origins and Evolution of Dayton’s Carillon Historical Park

The destination’s vice president of museum operations Alex Heckman and curator Steve Lucht wrote the 222-page, hardbound coffee-table book. READ MORE >>