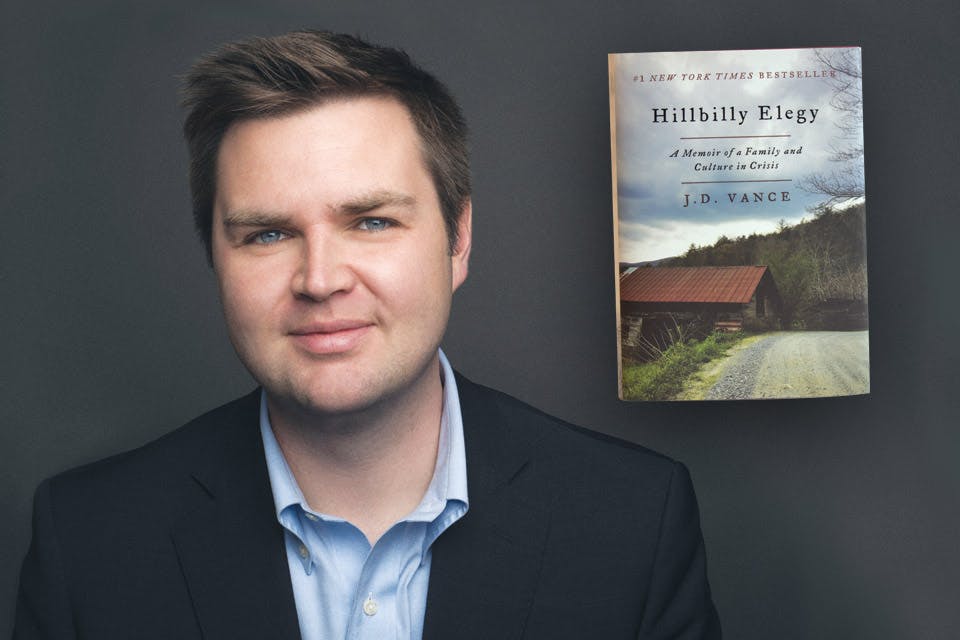

J.D. Vance on the Success of ‘Hillbilly Elegy’

The Ohio native talks about his best-selling book and how he hopes to use it as a way to improve the lives of people struggling with the same issues his family did.

September 2017

BY Linda Feagler | Photo by Luke Fontana

September 2017

BY Linda Feagler | Photo by Luke Fontana

J.D. Vance is living a version of the American Dream that’s easy to envy: After graduating from The Ohio State University in 2009 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science and philosophy, he headed to Yale University, where he earned his law degree in 2013 before landing a job as an investor at a venture capital firm in California’s Silicon Valley. Three years ago, he married a law school classmate, and the couple celebrated the birth of their first child in June.

But, Vance is quick to acknowledge, the scenario could have taken a different turn. The son of a mother who married five times and became addicted to drugs including heroin and a father who gave him up for adoption, Vance — who grew up in Middletown — was no stranger to the poverty and abuse that accompanied the loss of jobs and hope among residents. And yet, he counts himself among the lucky ones.

“I think a lot of people who grew up in circumstances like the one I grew up in didn’t have such a loving network of family to make sure the disadvantages they were born with didn’t consume them,” he says.

While in law school, Vance decided to share his story, hoping that it would shed light on how difficult the issues he grew up with really are. Since its debut last summer, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis has been a mainstay on The New York Times best-seller list. Ron Howard has signed on to direct and produce a movie adaptation, and the paperback version was released last month. On Oct. 6, Hillbilly Elegy will receive an Ohioana Book Award from the Ohioana Library Association at an awards ceremony in Columbus.

In February, Vance moved back to Ohio to launch Our Ohio Renewal, a nonprofit he says will “pursue government policies and private partnerships that make it easier for disadvantaged children to achieve their dreams.” Vance, 33, talked with us about his formative years, why the word “hillbilly” resonates with him and how we can help our country combat the problems he experienced growing up.

Was it painful to revisit the traumas of your early life?

It was certainly painful. But it was also cathartic to go back and think through some of those experiences and try to understand how they’ve affected me. As my wife, Usha, says, in some ways the book was like therapy for me — it was just therapy through writing as opposed to talking to someone.

Are you surprised by how successful the book has become?

I’m blown away. The initial print run was 10,000 copies, which I think gives you some sense of the expected readership. And we made it through those copies much more quickly than any of us expected. My grandest expectation for the book was that I could start an interesting conversation about upward mobility in the United States, that I could get people to look at the issues I wrote about through a new lens. I didn’t anticipate that it would be given such political relevance. Some people see it as a political manifesto which offers insight into the Trump voter. That always struck me as a little odd because I don’t even bring up Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump.

Where does the title come from?

I knew I wanted the word “hillbilly” to be in the title because it is [a term] that has a really rich meaning in my family. My grandma once said, “We can call ourselves hillbillies. But if anybody else calls you a hillbilly, then you should punch them in the nose.” It captures the fact that it is a term of endearment, but can also be viewed as a pejorative term when [the outside world] uses it. The “elegy” part of the title came during a series of conversations with my book agent, who suggested that the word captures the fact that the book is a little bit sad — not only because in a big-picture way I’m worried about some of the trends that exist in my community, but also in a very personal way because I talk about the death of my [grandparents] mamaw and papaw who were instrumental in making me the person I am today.

Your grandparents left Jackson, Kentucky, in the late 1940s and raised their family in Middletown, Ohio, where you grew up. Yet they saw themselves as hillbillies. What would you say the word “hillbilly” means to you?

I’d say it’s obviously somebody with some connection to the Appalachian Mountains, though I’ve learned that folks from the Ozarks and Arkansas also use the term. To me, it’s someone who has some connection to the hills, whether they’re in Missouri or whether they’re in eastern Kentucky. It also refers to someone who has a really deep love for the land and a certain pride in having come from that area. Sadly, though, there is a certain condescension that comes along with just being from that part of the world.

Would you say hillbilly cultures face distinct problems that other white working-class cultures do not?

Yes, I think that’s definitely true. You see it in the data that comes from the white working-class cultures in eastern Ohio or among the Appalachian migrants in southwestern Ohio: levels of addiction, family trauma, poverty. When we talk about the white working-class, we sometimes collapse it into this giant category where it means every white person without a college degree. But I do think it’s important to recognize that certain segments of the white working-class are struggling more than others, and you certainly see that when you go to these areas and talk to people and see how they’re living.

In the book’s Introduction, you mention that you “identify with the millions of working-class white Americans of Scots-Irish descent who have no college degree… To these folks, poverty is a family tradition.” Do the people you write about feel like victims?

In some cases they do and in some cases they don’t. An important tension that runs through the book is a recognition that some people face real disadvantage in their lives but they still have to try to do something with that disadvantage. If you completely give up on yourself, then you’re effectively dooming what little chance you have. And I worry that that sense of being a victim does exist in certain parts of the community. It’s not helpful, and it’s ultimately self-destructive.

How did you survive when other members of your family didn’t?

People ask, “What went right for you?” My answer to that is that 40 things went right for me, and I think that if you remove any one of them from the equation, I probably wouldn’t have done so well. Without my grandparents, I wouldn’t have had a happy home and a stable family, and we all know what happens to a lot of kids who lack those things. The United States Marine Corps, where I spent four years after graduating from high school, deserves a lot of credit for taking a kid who wanted to make something of himself but was a little unsure how to do it. My high school in Middletown was a really great school in a lot of ways, and I had teachers who took an interest in me and went the extra mile to ensure that I had a good education.

Did you ever feel like giving up?

There were definitely times when I looked at my life and didn’t think it was going to go especially well. When I was a freshman in high school, my grades were very bad, and I was pretty close to failing. I didn’t see a path forward for myself or any hope, which is very powerful in a bad way. That’s where having real mentors and family support can help. In some ways, it gives me chills thinking about what could have happened to that kid, given how unhappy and resentful he was.

You’ve experienced tremendous upward mobility. What might surprise people about what that feels like to you?

That I’m not comfortable with it all the time. [As a society], we think that if you go to a nice school and get a nice job, and have the white picket fence and two and a half kids and two dogs, everything is groovy. It’s true that my life is incredible, and I’ve been given a number of amazing opportunities. But I also think we have a big cultural disconnect in this country between those who are doing well and those who aren’t. If you go from poor to even middle-class in a rapid amount of time, you find that a lot of the things you grew up with are unfashionable or unhealthy in your new cultural group. It’s not just about not having money and then having money, it’s about occupying two totally different cultural worlds.

Early on in the book you mention, “For those of us lucky enough to achieve success, the demons of the life we left behind continue to chase us.” Do they for you?

Absolutely. The lessons we learn as children, the attitudes and habits we develop, don’t just disappear once you achieve some measure of upward mobility. You can’t just flick off the switch and unlearn every single lesson that you learned as a kid. I think that’s really important for us as a society to accept. That when we talk about people doing well, it’s not just in the material sense. Very often, what we’re trying to do is enable them to live a life they didn’t grow up knowing. It’s hard to give people good work who grew up in impoverished circumstances, but I think its even harder to teach those people habits of family stability and happiness that you don’t learn when you grow up in a family like mine. Being a good husband and father doesn’t come naturally to me because I didn’t see that growing up, and I will have to work on those skills for the rest of my life. But I think in some ways that’s a good thing because it’s always good to have a reminder of just how precarious happiness and stability can be and that you have to keep your head on straight or things can unravel pretty quickly.

You recently announced plans to create a nonprofit, Our Ohio Renewal. What will the organization’s mission be, and how do you hope to achieve it?

I decided to use the platform the book has given me to create an issues and advocacy organization. The idea for Our Ohio Renewal began with conversations I had with friends who said, “What would it look like if the people you are writing about in the book had their own lobbying firm? What would it look like if there was an organization dedicated to addressing their problems?” The first issue we’re going to tackle is the issue of kinship care in Ohio. Folks who know the opioid crisis know it’s actually made a lot of kids homeless and created a lot of burdens for grandparents and aunts and uncles who find themselves taking care of children they didn’t expect to take care of. These people need financial resources, as well as a legal system that’s more responsive to their concerns.

What advice do you have for politicians who say they’re dedicated to solving the problems in your community that need to be fixed?

Don’t legislate from on high. Actually get to know these people before making policies that are going to affect their lives.

Any thoughts of running for office yourself?

You never say never, but it’s certainly not something that I think about doing right now. There’s enough going on elsewhere.

The Ohioana Book Awards will take place Oct. 6 at the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus. The event includes a reception with hors d’oeuvres and refreshments and an awards presentation. Admission is $50 and reservations are required. For more information about the event, visit ohioana.org.

Related Articles

Cincinnati Writer and Musician Nick Greenberg Talks Fungi Fiction

The classically trained musician in a variety of styles also had a stint in the food industry, which he draws from for his novels that feature culinary capers. READ MORE >>

2025 Ohio Book Award Winners Announced

These annual awards from the Ohioana Library honor Ohio-centric books. They will be presented Oct. 15 at the Ohio Statehouse. READ MORE >>

Enjoy Books and Brews at These 3 Ohio Shops

Visit these three Ohio bookstores that go beyond the printed page to offer coffee, beer, wine and more. READ MORE >>