How Ohio Stadium’s Opening Ushered in a New Era of Sports

The Horseshoe was dedicated on Oct. 21, 1922. The moment marked the rise of both Ohio State Football and the construction of new stadiums across the nation.

Sept./Oct. 2022

BY Vince Guerrieri | Photo courtesy of The Ohio State University Archives

Sept./Oct. 2022

BY Vince Guerrieri | Photo courtesy of The Ohio State University Archives

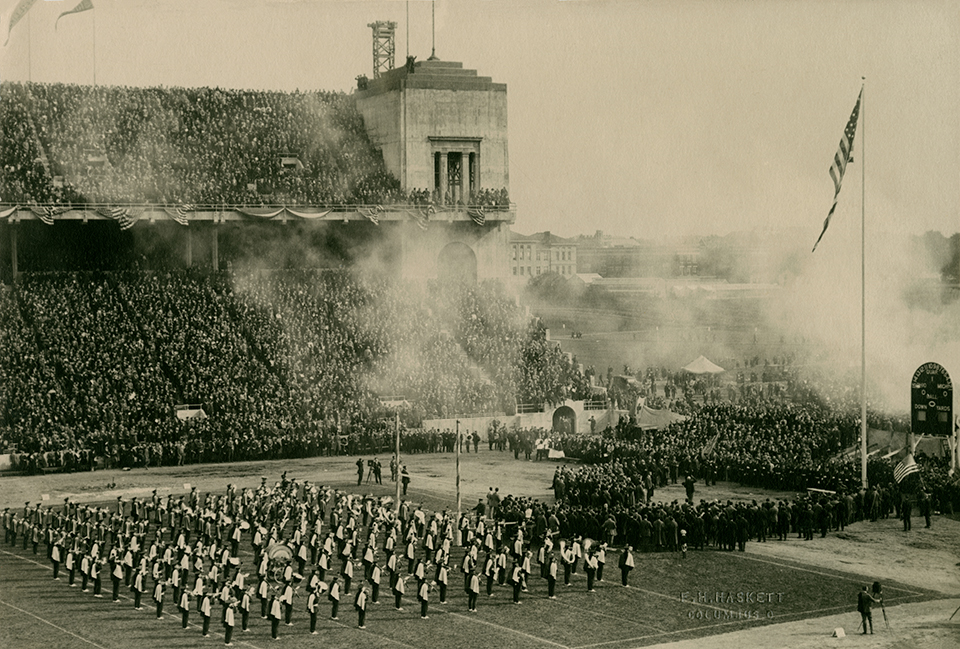

Scores of dignitaries, including the governors of Ohio and Michigan — the Buckeyes’ opponent that day was the Wolverines, after all — trod across the grass of the new stadium, as representatives of each of the 10 schools of what was then known as the Western Conference (Iowa, Chicago, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Northwestern, Indiana and Purdue, along with Ohio State and Michigan) raised flags to the top of the stadium’s facade. A cannon fired a volley, both schools’ bands played, and a new era in spectator sports dawned on the banks of the Olentangy River.

“Words in Old Noah Webster’s dictionary, unless thrown together by a William M. Thackeray or a John Milton, fail to adequately express what took place in the dedication of the Ohio stadium at Columbus this afternoon,” reporter Jack Myers wrote for the next day’s Dayton Daily News.

The new Ohio Stadium was a significant evolutionary step in sports fans gathering in enormous numbers. Certainly, there had been marquee events that drew tens of thousands of spectators before: The year before, more than 80,000 people traveled to a spot in Jersey City, New Jersey, called Boyle’s Thirty Acres to watch Jack Dempsey defend his heavyweight boxing title against Georges Carpentier. But that arena — like the one built for the 1919 fight in Toledo where Dempsey battered Jess Willard to claim the heavyweight crown — was a temporary one, erected and then torn down six years later.

Ohio Stadium, the biggest stadium in college football with an official capacity of more than 66,000 fans, would be permanent. Newspaper accounts of the day compared the new venue to the Colosseum, but it was even bigger than Rome’s famous oval amphitheater — thanks in part to the curved upper deck that led coverage of the opening to refer to it as a “horseshoe.” And, as Ohio Stadium’s contractor noted during the dedication ceremony program, it was completed more quickly.

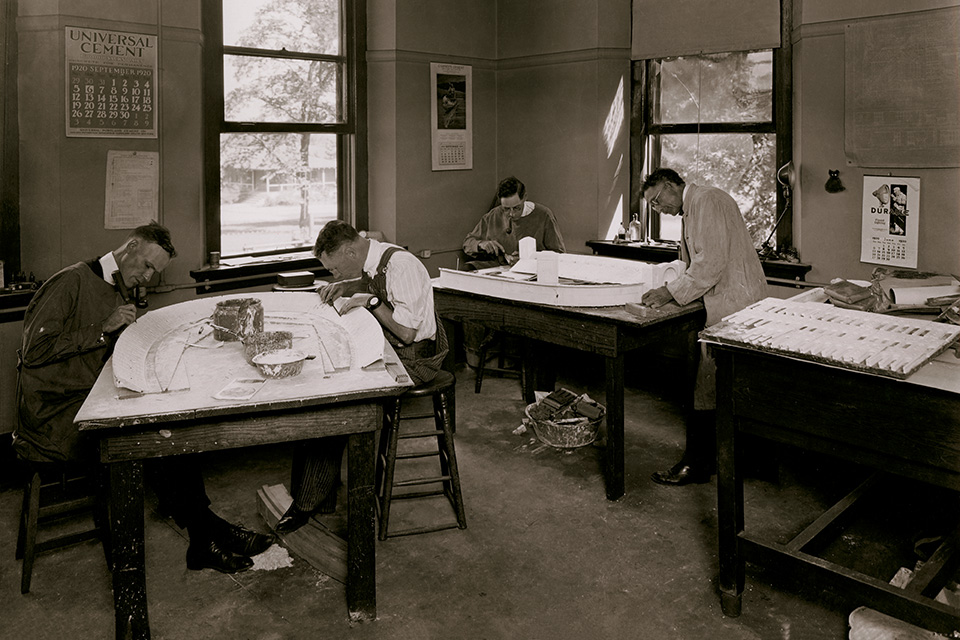

Drafters work on a model of Ohio Stadium in 1920. (photo courtesy of The Ohio State University Archives)

On the day it opened, crowds exceeded 71,000 spectators, including more than 15,000 Michigan fans who had traveled south for the game. Although the stadium was able to accommodate everyone, getting them there and back turned out to be a challenge. Crowds streamed into the stadium up until the start of the game, and Columbus’ Union Station reported the busiest day in its history, with thousands of riders thronging the place — to the point where taxis parked nearby were immobilized. It was a rare issue in what to that point had been a largely smooth and trouble-free process.

“The stadium has been built without controversy,” Ohio State University President William Oxley Thompson noted at the dedication, “without ill will and with that kind of cooperation which rendered every service a delight.”

***

What’s regarded as the first football game ever played was also the first college football game ever played. In 1869, Rutgers University and the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) met in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Rutgers won, 6-4, and as the score indicates, the game bore little resemblance to today’s football, combining elements of English soccer with rugby. Seven years later, the first modern rules of the game were drawn up at the Massasoit Convention in Massachusetts by representatives from Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Columbia.

Those four schools would dominate the early landscape of college football. When Damon Runyon, one of the pre-eminent sportswriters of his day, covered college football, it was Harvard and Yale. A young Princeton graduate named F. Scott Fitzgerald made college football a backdrop throughout many of his novels and short stories.

The Oct. 21, 1922 dedication was filled with pageantry (above). The Buckeyes played the University of Michigan that day. (photo courtesy of The Ohio State University Archives)

Then, football moved inland. The University of Michigan played Racine College in the first Midwestern football game in 1879, and many of the new land-grant colleges throughout the Midwest started to field football teams, too, including Ohio State University, which played its first football game on Nov. 1, 1890, against the College of Wooster. It was an inauspicious debut for Ohio State, which lost 64-0.

In fact, Ohio State was largely a mediocre program until the arrival of Charles Wesley Harley in 1916. Chic (his nickname came from his Chicago birthplace and his family moved to Columbus when he was a youth) dazzled fans with his play. His games at Columbus’ East High School regularly outdrew Ohio State football games. After high school, Harley ended up at Ohio State and instantly made a difference, leading the football team to two straight undefeated seasons, winning the conference each year.

Author James Thurber, one of Harley’s contemporaries at Ohio State, said the star’s style of play, “Was kind of a cross between music and cannon fire, and it brought your heart up under your ears.”

Suddenly, thousands of fans wanted to watch Ohio State football. That point was hammered home in Ohio State’s regular season finale in 1919. Harley had left the team during the 1918 season to join the military in World War I, but he then returned the following year to lead Ohio State to another undefeated season going into the last game of the year.

Then as now, Ohio State ended each season with a rivalry game, but at the time, the Buckeyes’ big rival was the University of Illinois. The Illini won 9-7 on a last-second field goal, handing Harley his only collegiate loss. More than 15,000 fans turned out for the game, and an estimated 25,000 more were turned away. Clearly, a new facility was needed, and as luck would have it, Ohio State had someone on faculty who could make it happen.

The Buckeyes played the University of Michigan Wolverines — prior to the rivalry it has become today — during the dedication day game. Ohio State lost 19-0. (photo courtesy of The Ohio State University Archives)

Howard Dwight Smith was a Dayton native who grew up near the Wright brothers’ bicycle shop. He became the first member of his family to go to college and graduated from Ohio State with an architecture degree in 1907. He then studied at Columbia and spent a year in Europe before returning to Ohio. He designed schools and government buildings in Columbus and in 1918 was hired as an architecture professor at his alma mater.

Plans for the new stadium were ambitious. Its seating capacity would surpass that of the Yale Bowl, at the time the largest stadium in America, with capacity for more than 60,000 fans. Fundraising started in 1920, with the initial $1 million goal for construction pledged within three months. “We’re going back to State to help build Ohio Stadium,” said stickers emblazoned on Ohio State students’ luggage. Undergraduates at the university alone pledged $100,000 toward construction.

Workers excavated and poured concrete around the clock, with large floodlights illuminating the site. (Ironically, the first night game at Ohio Stadium wouldn’t come until 1985, and lights weren’t permanently installed at The Horseshoe, as it came to be known, until a 2014 renovation.)

The stadium was approximately a third of a mile long and 107 feet high, constructed with 14,000 tons of cement, 17,000 tons of sand, 33,000 tons of gravel and 43,000 tons of steel. The Dayton Herald trumpeted the day before the stadium’s dedication, “It is probably the greatest example of college architecture in the world.”

***

An aerial view of Ohio Stadium from the 1990s (photo courtesy of The Ohio State University Archives)

After all the pomp and circumstance, Ohio State laid an egg in Ohio Stadium’s dedication game. Michigan All-American halfback Harry Kipke scored a touchdown on offense and then intercepted Hoge Workman for another score. The Wolverines won 19-0 to run their record against their rival to 14-3-2. The loss in 1922 was the start of a six-game skid against Michigan for the Buckeyes.

But the results of the new facility were undeniable. More than 250,000 fans had come to Ohio Stadium to watch the team during the 1922 season, exponentially more than before. An arms race was at hand for stadium construction.

In the Bronx, a new baseball stadium was being built for the New York Yankees. If Ohio Stadium was the House Chic Harley Built, this would be the House that Ruth Built. In Chicago, a new stadium would soon rise on the Lake Michigan shoreline — named Soldier Field in honor of World War I veterans — and city fathers in Philadelphia envisioned a massive stadium that would open in America’s sesquicentennial year of 1926. On the West Coast, construction was underway for a new stadium in Pasadena for the Rose Bowl game as well as an expansion to the Coliseum in Los Angeles for the 1932 Olympics. Even Michigan decided a newer, bigger house was needed.

Gradually, Ohio State’s football team got it together. Francis Schmidt, a mad genius whose offensive prowess coaching Texas Christian and Arkansas led to the nickname “Close the Gates of Mercy,” was hired as Ohio State coach in 1934. He said that Michigan players “put their pants on one leg at a time, just like the rest of us.” Ohio State then went out and beat the Wolverines 34-0, the first of four successive shutouts by Ohio State of their rivals to the North. (To this day, Ohio State players who are part of a team that beat Michigan get “the golden pants,” a gold charm of a pair of pants, recalling Schmidt’s words.)

Schmidt won two Western Conference titles with Ohio State before he was succeeded by an Ohio native whose coaching career was on the rise: Paul Brown. The future Browns coach and Bengals founder would lead Ohio State to its first national title in 1942. After Brown had gone on to pro football, Ohio State hired Woody Hayes from Miami University (Brown’s alma mater), who entrenched the Buckeyes among college football’s elite programs.

Ohio Stadium is one of college football’s most famous venues. (photo by iStock)

Today, the Buckeyes remain a perpetual power, and Ohio Stadium has become one of the largest venues in college football. The stadium’s original design allowed for temporary bleachers in the open end of the horseshoe. Gradually, those became permanent, with a capacity of more than 80,000 by the 1960s (although unofficially, Michigan games had crowds that were 90,000 or more). Another major renovation in 2001 eliminated the track around the football field (that was when Jesse Owens Memorial Stadium was built on campus), allowing for more seats, and as the 21st century dawned, Ohio Stadium could hold more than 100,000. The record for attendance was more than 110,000 against yep, you guessed it, Michigan, but official capacity is north of 102,000.

The capacity wouldn’t exist without the demand. Ohio State fans had become a rabid bunch, profiled by Life Magazine in 1948, and it didn’t take long before Columbus was called the football capital of America — thanks in no small part to its stadium, which “towers over the campus as much as the Empire State Building dominates the New York skyline,” John Scanlon wrote for the Saturday Review in 1962, a statement that’s no less true now. “When a visitor beholds it for the first time, he is immediately struck by its awesome majesty.”

Related Articles

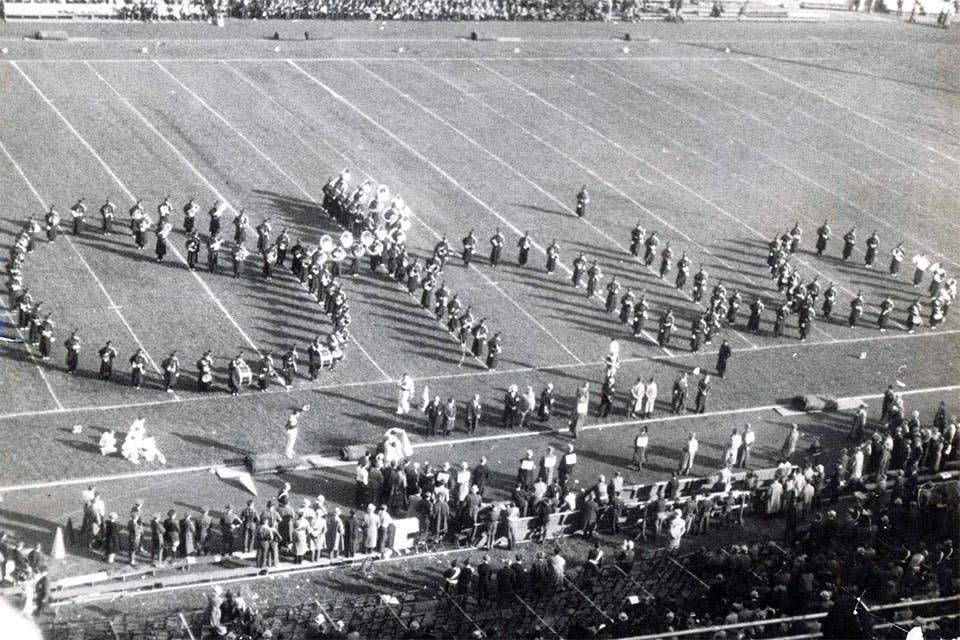

The Ohio State Marching Band Performs First Script Ohio

In 1936, band director Eugene Weigel’s vision for a smooth and flowing formation made its debut at Ohio Stadium in October of that year. READ MORE >>

_recto.jpg?sfvrsn=c212b438_5&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

How Forgotten Songwriter Ernest Ball Rose to Fame

He isn’t a household name these days, but it’s estimated that the Cleveland native penned over a thousand songs, including Irish-themed standards that are still sung each Saint Patrick’s Day. READ MORE >>

Cold War Discovery Center Opens in Dayton

A new permanent exhibition at Carillon Historical Park examines the city’s rich history in secret research that included work on the atomic bomb. READ MORE >>