Arts

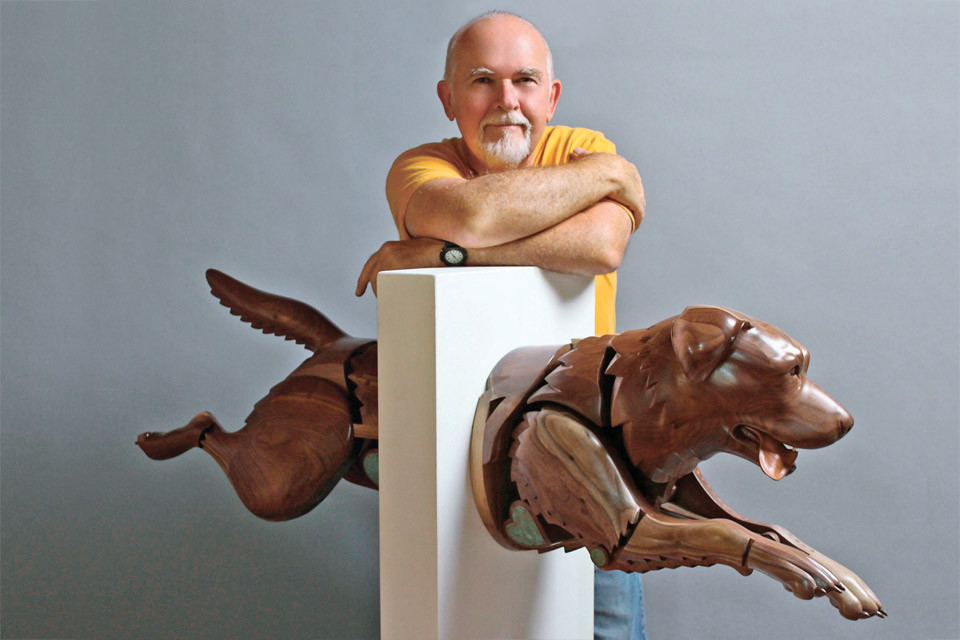

The Art of James Mellick’s Wounded Warrior Dogs Project

James Mellick’s sculptures are poignant works that reflect the courage and sacrifice of those who serve to protect our freedoms.

Related Articles

See ‘Tony Foster: Exploring Time, A Painter’s Perspective’ in Dayton

Artist Tony Foster examines both the enormity and fleeting nature of time with his watercolor paintings. An exhibition of his work opens at the Dayton Art Institute on Feb. 21. READ MORE >>

Restoration Begins on George Sugarman’s ‘Cincinnati Story’ at Pyramid Hill Sculpture Park

The colorful, iconic sculpture is undergoing restoration ahead of a 2026 public rededication. READ MORE >>

Step Inside Cleveland’s Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument

This historic monument on Public Square commemorates the sacrifice and service displayed by Cuyahoga County residents during the Civil War. READ MORE >>