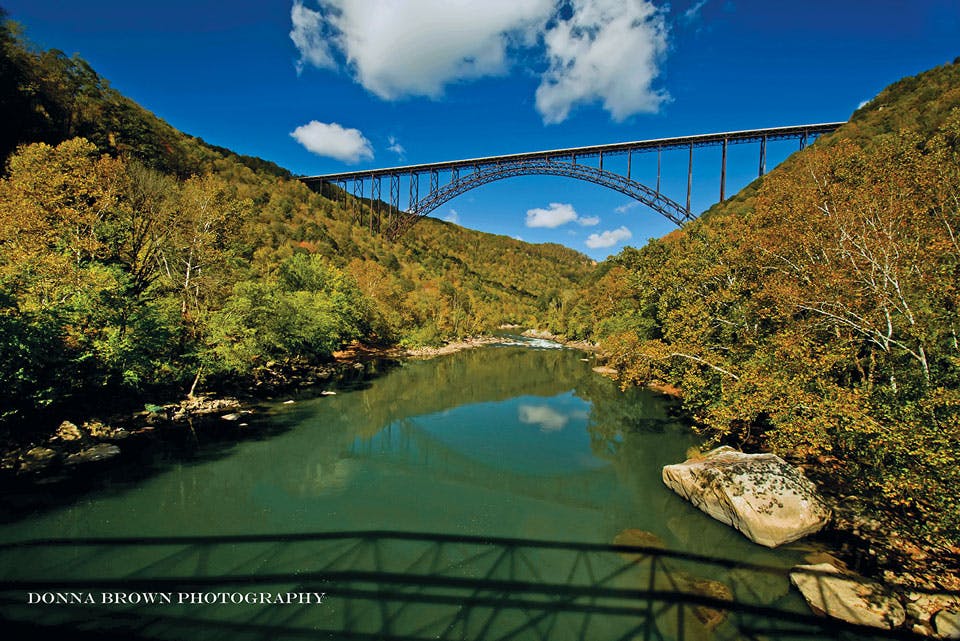

West Virginia: 5 Fascinating Finds

From a secret government bunker to a re-creation of an early 20th-century mining town, get a new perspective on the Mountain State at these spots

Related Articles

Visit These 4 Kentucky Bourbon Distilleries

From Bluegrass State legends that have been around for generations to newer destinations with their own approach to crafting bourbon, check out these four distinct distillery experiences. READ MORE >>

13 Ways to Enjoy Fall in Grove City, Ohio

From a pizza trek and wing festival to an expansive paintball park and historic gardens, this Columbus suburb offers a variety of adventures. READ MORE >>

5 Scenic Driving Routes in West Virginia

Explore five picturesque drives that show off the beauty, history and opportunities for outdoor adventure that make the Mountain State a summer draw. READ MORE >>