Why Sherwood Anderson’s ‘Winesburg, Ohio’ Created an Uproar in His Hometown

The author’s 1919 cycle of short stories is a literary classic. But when it was published in 1919, it caused a stir in Clyde, Ohio, where many believed the work of fiction was spilling the town’s secrets.

December 2019

BY Kristina Smith | Photo by Bianca Garza

December 2019

BY Kristina Smith | Photo by Bianca Garza

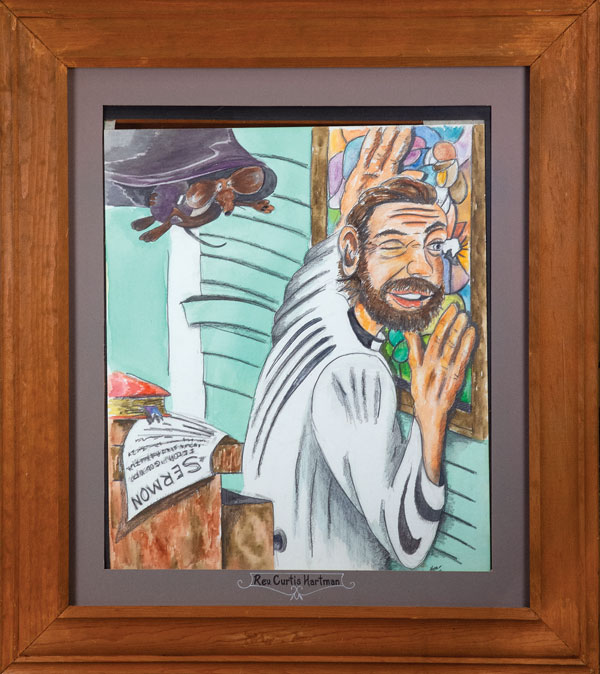

The Rev. Curtis Hartman was a quiet, resolute man who went to a small room in the church tower each Sunday to pray and prepare his weekly sermon. But one morning, as he gazed through the tower window into a neighboring home, he witnessed a shocking scene: a town schoolteacher sitting on her bed smoking a cigarette — her shoulders and throat bare.

It was the 1890s after all, a time when women customarily wore long, high-necked dresses with bustles, and in Hartman’s eyes, the schoolteacher was a woman “far gone in secret sin.” Still, that didn’t stop him from his ritual of climbing to the top of the church tower. Only now he was longing to spy the woman’s bare neck and shoulders, as he tried desperately to repress his lustful thoughts and the growing resentment he felt toward his conservative wife.

Soon, he began sneaking into the tower at night to watch the woman. Afterward, he would walk the city streets, asking God to help him in his struggle. One frigid January evening, he decided he could no longer fight temptation. So, the preacher again went to the freezing bell tower and sat waiting for the woman to return. But this time, she entered the room and threw herself naked onto the bed, crying and hitting the pillows. She was dealing with a struggle of her own: Longing for someone to love, she had just kissed one of her former students — a young man she was trying to mentor. After realizing what she had done, she fled to her room to wallow in her pain.

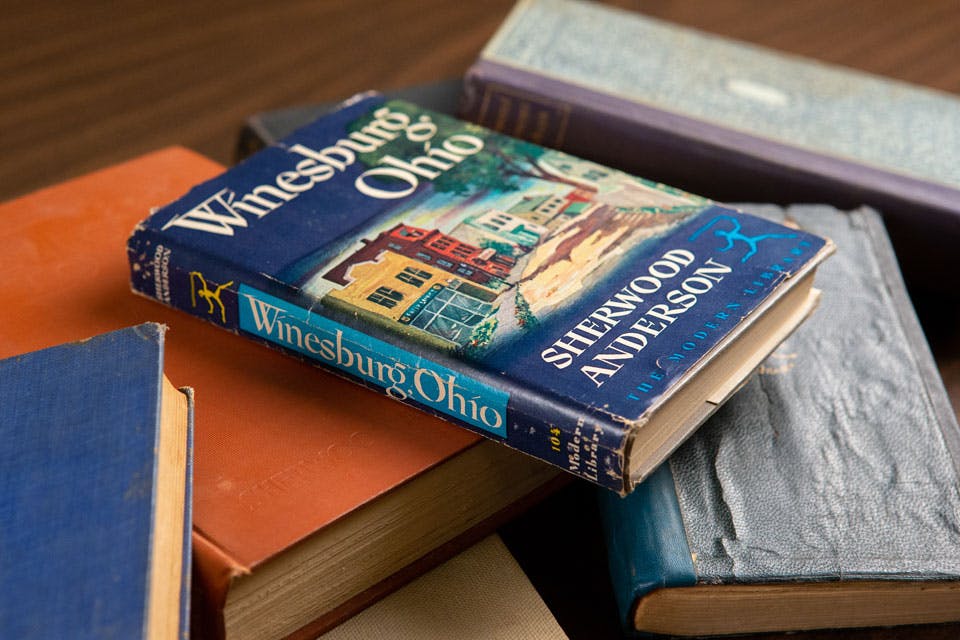

The two characters appear in author Sherwood Anderson’s 1919 literary classic Winesburg, Ohio. The author had originally wanted to call it The Book of the Grotesque, but his publisher convinced him to opt for something a bit more marketable.

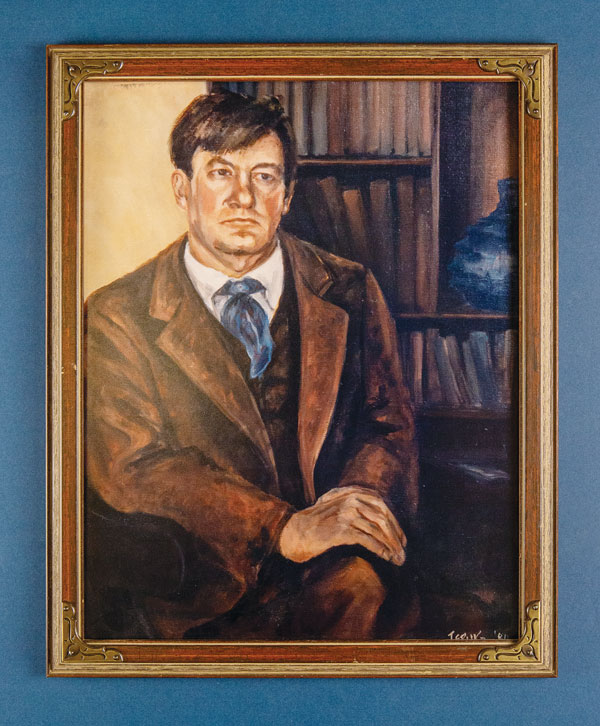

Sherwood Anderson was lauded by some critics are the father of realism, a new genre of writing. (photo courtesy of Hayes Presidential Library & Museums)

When Winesburg, Ohio was published, some critics lauded Anderson for being the father of realism, a new genre of writing. Although the author had penned other works, this was the first to receive national attention and solidify him as a well-known writer.

Still many people of the era considered the book scandalous, and the vitriol aimed at Anderson was perhaps strongest in his Sandusky County hometown of Clyde, Ohio. The problem was the work of fiction seemed familiar to locals — maybe a little too familiar — and none of them appreciated their town’s secrets, whether factual or embellished, being aired to the world.

***

Winesburg, Ohio remains a literary classic to this day and is still taught in colleges around the world. Anderson’s writing also influenced literary legends to follow such as William Faulkner, John Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingway. At the time of the book’s release though, the public largely hated it. Stories that delved into people dealing with sexual repression, unfulfilled dreams and the inability to communicate their feelings with those closest to them was shocking at the time.

The problem was the work of fiction seemed familiar to locals — maybe a little too familiar — and none of them appreciated their town’s secrets, whether factual or embellished, being aired to the world. (photo by Bianca Garza)

When Anderson chose Winesburg as the stand-in name for his hometown of Clyde, he didn’t realize there actually was a real Winesburg, Ohio. Those who lived there weren’t fans of his book either. But the problem in Clyde went deeper, with many of the characters in the book resembling actual residents of the town.

“People would read this book and say, ‘Wait a minute! That’s so-and-so,’” says Gene Smith, curator of the Clyde Museum. “It shocked them that he would write about people he knew. They portrayed a certain image in public, and he looked beyond that to who they really were.”

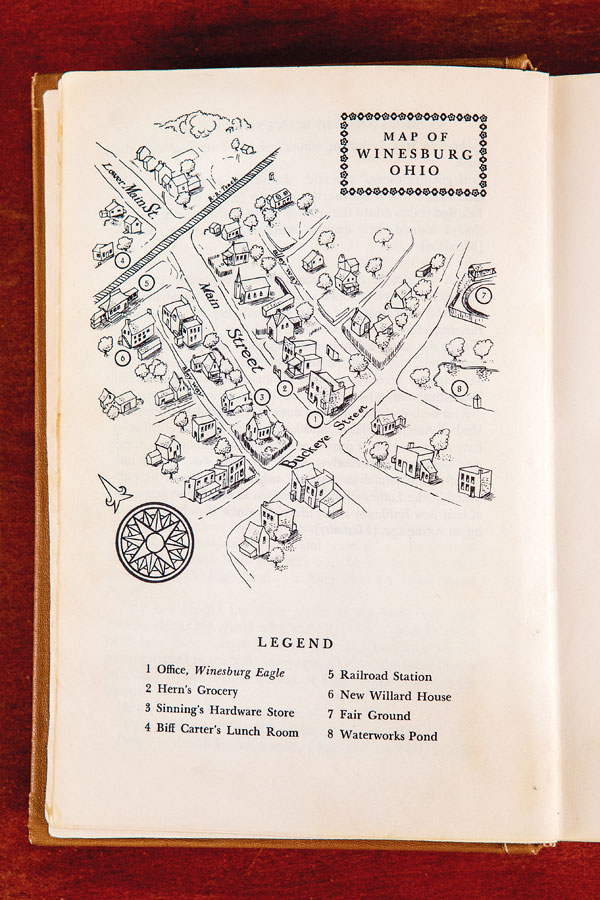

The literary town’s geography also was unmistakably Clyde. Some editions of the book even included a map of the fictional Winesburg, Ohio, which had some of the same street names and a similar layout.

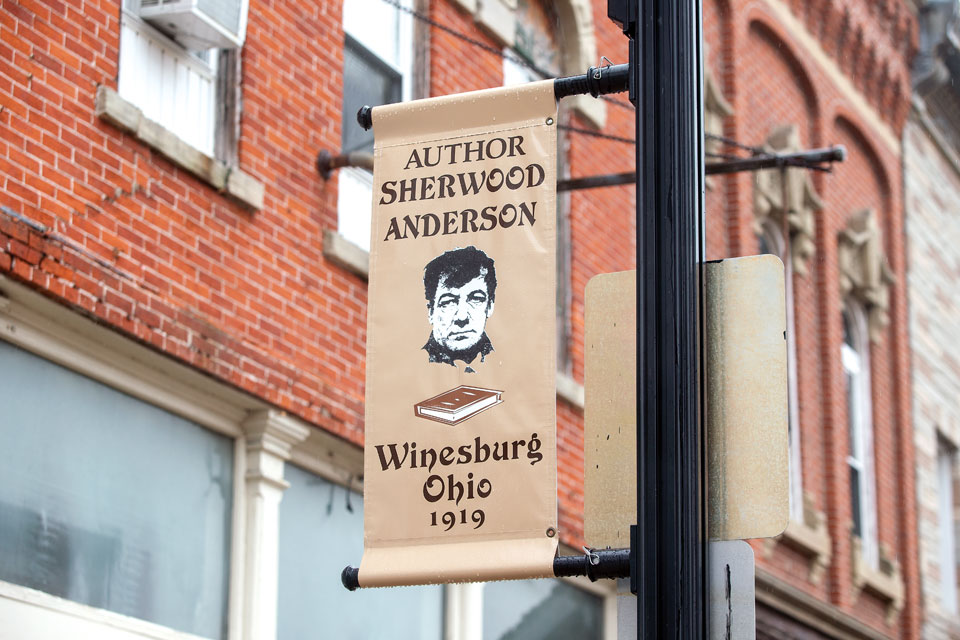

Signs in Clyde celebrate its ties to Sherwood Anderson. (photo by Bianca Garza)

Although Anderson was born in the Preble County village of Camden, the author spent his formative years in Clyde. His family moved there in 1884, when Anderson was 8, and he lived there until he moved to Chicago at age 20. His father was a Civil War veteran who drank and had trouble keeping steady work. His mother was the breadwinner, taking on laundry and sewing jobs to support the family. Known locally as “Jobby,” Anderson would accept whatever odd jobs he could find, be it delivering groceries or chopping wood, to help his family get by.

Perhaps his memories of growing up poor in a small town during the horse-and-buggy era are one of the reasons he based the book in Clyde and used the 1890s as the setting. Scholars believe the young newspaper reporter and town confidante in the book, George Willard, is Anderson himself. Anderson’s parents are believed to be Elizabeth Willard — the sick and lonely woman trapped in the shabby hotel she inherited from her father — and her husband.

Anderson was confused by the negative reception Winesburg, Ohio received upon its release on May 8, 1919.

“The book had been so personal to me that, when the reviews began to appear and I found that, for the most part, it was being taken as the work of a perverted mind ... it was called ‘a sewer’ and the man who had written it taken as a strangely sex-obsessed man ... a kind of sickness came over me, a sickness that lasted for months,” Anderson wrote in his 1942 memoirs.

Sherwood Anderson’s hometown of Clyde carries pride for the author behind “Winesburg, Ohio.” (photo by Bianca Garza)

No matter Anderson’s view about Winesburg, Ohio, the people of Clyde felt betrayed. Thaddeus Hurd, who had an aunt Anderson once sought to marry, told the Toledo Blade in 1970 that his aunt liked the author very much — until the book came out.

“She used to get purple in the face telling me how dirty that book was,” Hurd told the newspaper. “The townswomen were vitriolic about Sherwood’s writing, the men called it ‘gloomy,’ and my aunt went to her grave hating him.”

When Anderson visited his hometown after the book was published, he showed up at a party at one of Clyde’s stately homes, hoping to reconnect with old friends and acquaintances. According to local lore, the hostess turned him away, saying, “You’re not welcome here.”

The Clyde Public Library even supposedly banned Winesburg, Ohio for many years, and some newspaper articles even refer to townspeople burning it. Library staffers have found no evidence that either of these oft-told stories is true, according to library director Beth Leibengood. But the fact that these tales persist a century later shows how deep the bad feelings toward Anderson and his book once ran in Clyde. But were the stories of his characters’ secret struggles really based on those who lived there? Even Anderson’s own letters and memoirs don’t offer a clear answer.

In a November 1916 letter to his friend and magazine publisher, Waldo Frank, three years before Winesburg, Ohio was published, Anderson outlined the inspiration for it.

“I made last year a series of intensive studies of people of my hometown, Clyde, Ohio,” Anderson wrote. “In the book I called the town Winesburg, Ohio. Some of the studies you may think pretty raw, and there is a sad note running through them. One or two of them get pretty closely down to ugly things in life. ... When these studies are published in book form they will suggest the real environment out of which present-day American youth is coming.”

A painting of the author hangs in the Clyde Public Library. (photo by Bianca Garza)

But in his 1942 memoirs, Anderson seemed to contradict that 1916 letter: “It was a mythical town. It was people. I had got the characters of the book everywhere about me, in towns in which I had lived, in the army, in factories and offices.”

Will Schuck, a Sherwood Anderson scholar based in Columbus, doesn’t think the characters in Winesburg, Ohio were necessarily based on the residents of Clyde.

“There’s no way he could have picked up all those details about people’s lives when he was a child,” says Schuck, who founded the Sherwood Anderson Literary Center, an online resource that promotes the author’s works. “That wasn’t the only place he lived. Those were people in situations that he was writing about as an adult. I believe they were based on experiences that he witnessed living and working in Chicago, living and working in Cleveland, living and working in Elyria.”

***

As the years passed, anger toward Anderson from those in Clyde subsided. The outrage began to dissipate in the 1970s, as those who remembered Anderson, the book and the people portrayed within its pages died. Residents of Clyde also realized having an acclaimed author as a native son was something to embrace.

Despite his aunt’s hatred of Anderson, Hurd appreciated the author’s literary contributions enough to donate money to the Clyde Museum and Clyde Public Library to preserve his legacy. The sections at each site reserved for Anderson’s works and artifacts are named for Hurd — a historian and architect who died in 1989. He was believed to be the last Clyde resident with any direct connection to Anderson or the book.

Artist Kenn Bower’s depictions of several of the characters featured in “Winesburg, Ohio” are on display at the Clyde Public Library.

In 1979, Anderson’s fourth wife, Eleanor Anderson, was welcomed to Clyde to celebrate what would have been the author’s 103rd birthday. Four years later, Anderson’s daughter, Marion “Mimi” Anderson Spear, received a warm welcome when she visited. Throughout 2019, Clyde celebrated the 100th anniversary of the book’s first publication, and an Ohio Historical Marker stands prominently in a downtown park.

“The city loves claiming Sherwood Anderson,” Leibengood says. “When people [in Clyde] hear references to [his book], they’re happy to claim it and are proud that it’s about their town.”

Schuck says the author’s style of storytelling still resonates because the situations the characters dealt with remain relevant today. His literary realism was new for the era, but it also shined a light on mental health and depression — things that weren’t discussed at the time.

Anderson himself led a complicated and sometimes unhappy life. As an adult, he struggled with working at a Chicago ad agency and then managing a successful paint company in Elyria to pay the bills while really wanting to concentrate on writing. Although he was an acclaimed author, his works didn’t pay enough for him to solely be a writer until much later in life. He was married four times and suffered a nervous breakdown.

“I don’t think Sherwood Anderson was purposely trying to be risque when he wrote this book,” Smith says. “I think he was trying to examine how life really is. When you consider how he was raised and his life, you begin to understand why he wrote the way he did.”

Anderson died in 1941 in Panama while on a cruise to South America. Even his death was unusual. He had swallowed a toothpick that caused peritonitis — inflammation of the abdomen. Still, his literary legacy lives on in Clyde, where Winesburg, Ohio researchers and fans come to visit the Sherwood Anderson collections at the local museum and library. Leibengood says the book is especially popular in Asian countries and some of the library’s collections of Anderson’s works have been translated into Japanese to better accommodate researchers.

“He did have a huge impact on literary realism,” Smith says. “He did have an impact on mental health. He was willing to talk about these things when no one else really was. That’s why he shouldn’t be ignored or forgotten.”

Related Articles

Cold War Discovery Center Opens in Dayton

A new permanent exhibition at Carillon Historical Park examines the city’s rich history in secret research that included work on the atomic bomb. READ MORE >>

See Ohio in a New Way at These Six Historic Sites

In celebration of Ohio Statehood Day on March 1, we share six places, artifacts and landmarks that illuminate history and help us see our shared heritage in new ways. READ MORE >>

Cincinnati Writer and Musician Nick Greenberg Talks Fungi Fiction

The classically trained musician in a variety of styles also had a stint in the food industry, which he draws from for his novels that feature culinary capers. READ MORE >>