The Legacy of Master Carver Ernest Warther

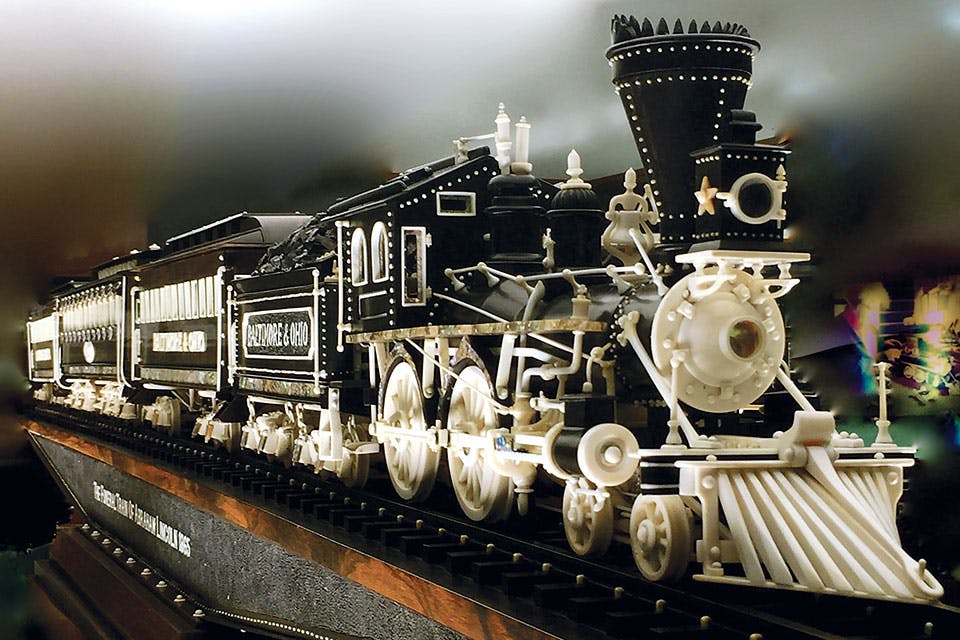

Ernest Warther’s formal education ended in second grade, but his ability to make elaborate, hand-carved depictions of trains from the steam-locomotive era cemented him as a genius in his own right.

Related Articles

See the World’s Largest Collection of Lithophanes at this Ohio Museum

The Blair Museum of Lithophanes at the Schedel Arboretum & Gardens in Elmore is dedicated to the 19th-century art form, housing more than 2,300 unique pieces. READ MORE >>

See Ohio in a New Way at These Six Historic Sites

In celebration of Ohio Statehood Day on March 1, we share six places, artifacts and landmarks that illuminate history and help us see our shared heritage in new ways. READ MORE >>

.jpg?sfvrsn=21d9b438_3&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Discover 3 Newly Recognized Underground Railroad Sites in Appalachian Ohio

The National Park Service has recently acknowledged three Ohio communities that played a role in helping Civil War-era freedom seekers. READ MORE >>