Ohio Life

Revisiting Ohio’s Bygone Department Stores

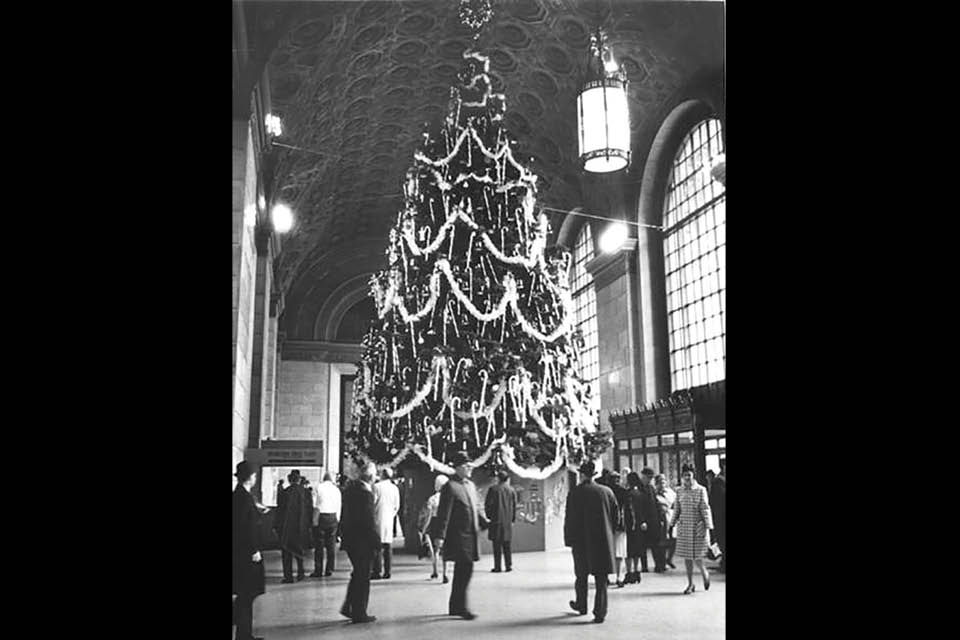

Department stores once ruled the retail landscape with their wealth of offerings and festive approaches to the holidays. These four are long closed, but the memories of them still burn brightly.

Related Articles

.jpg?sfvrsn=21d9b438_3&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Discover 3 Newly Recognized Underground Railroad Sites in Appalachian Ohio

The National Park Service has recently acknowledged three Ohio communities that played a role in helping Civil War-era freedom seekers. READ MORE >>

Learn the Sweet History of The Dawes Arboretum at Maple Syrup Day

The Newark arboretum’s founders, Beman and Bertie Dawes, began harvesting sap for maple sugar in 1919. Today, the annual Maple Syrup Day shares that heritage with visitors. READ MORE >>

New Book Details Origins and Evolution of Dayton’s Carillon Historical Park

The destination’s vice president of museum operations Alex Heckman and curator Steve Lucht wrote the 222-page, hardbound coffee-table book. READ MORE >>

.jpg?sfvrsn=99bc38_7&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

.jpg?sfvrsn=e899bc38_7)