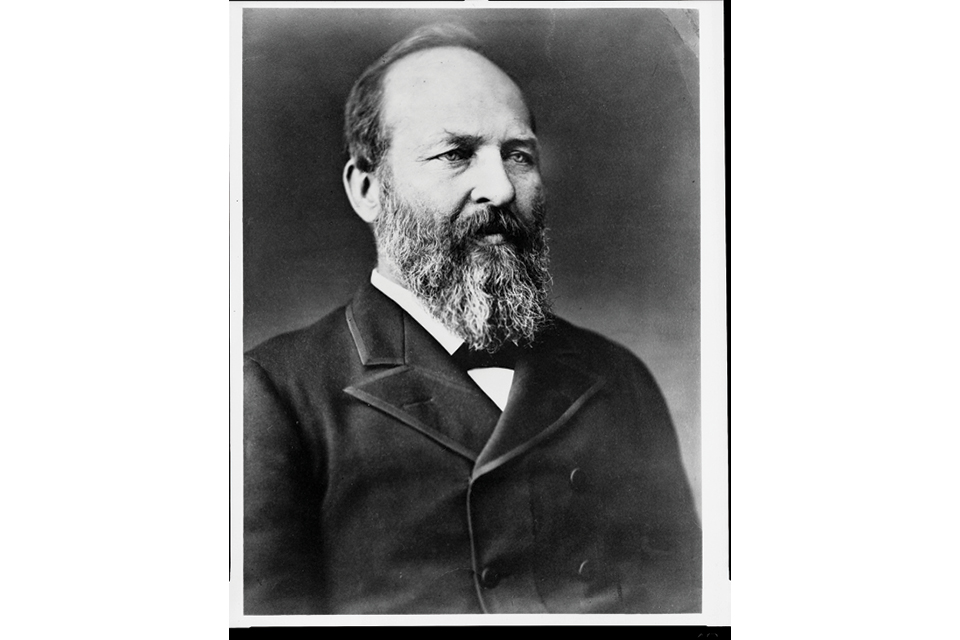

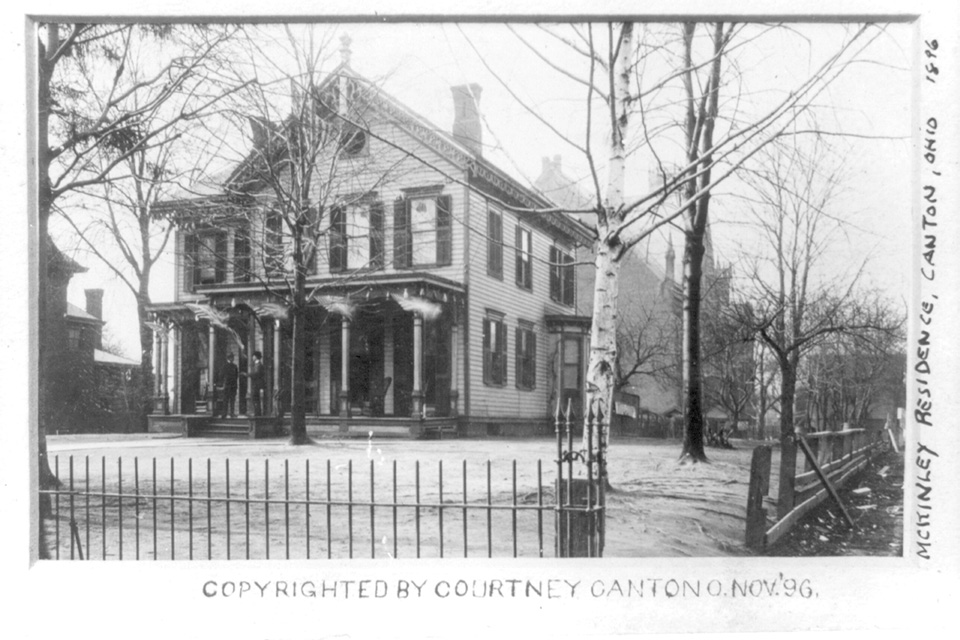

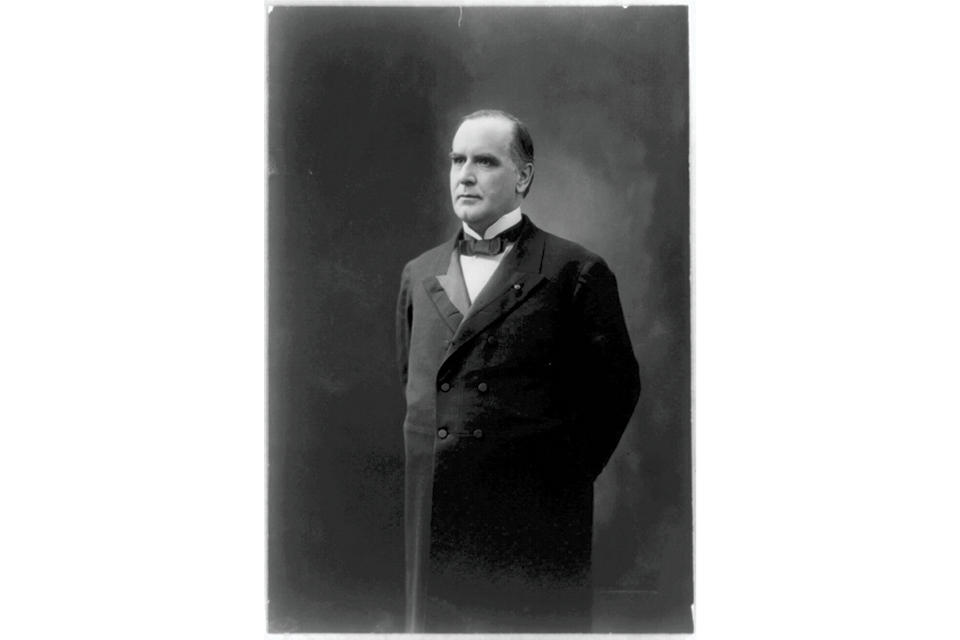

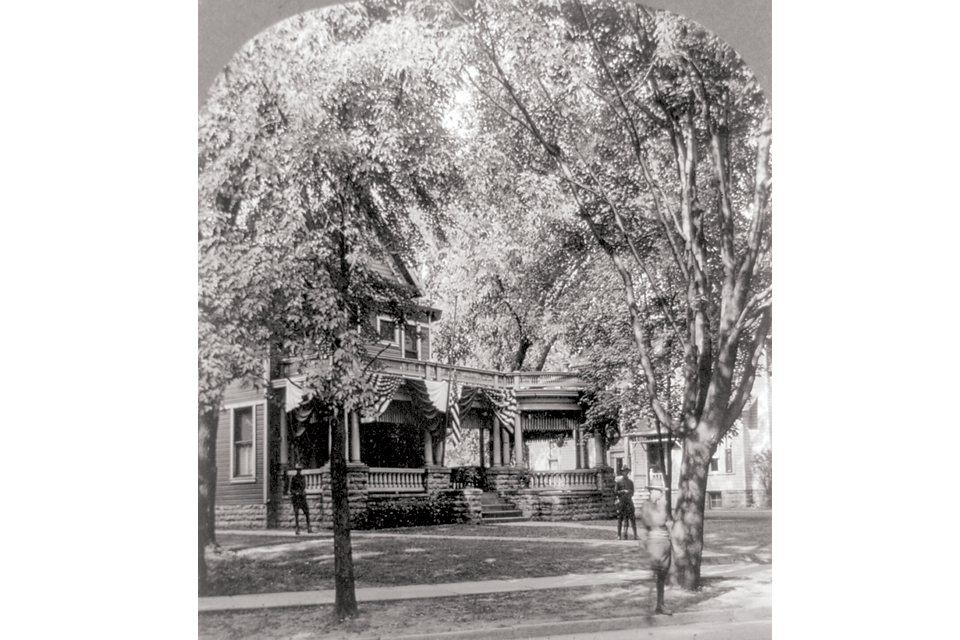

How Garfield’s Front Porch Changed Campaigning for President

Before whistle-stop tours and crisscrossing the country, presidential candidates spoke to crowds at their own homes. Here’s how three Ohioans used the approach to win our nation’s highest office.

Related Articles

Cold War Discovery Center Opens in Dayton

A new permanent exhibition at Carillon Historical Park examines the city’s rich history in secret research that included work on the atomic bomb. READ MORE >>

See Ohio in a New Way at These Six Historic Sites

In celebration of Ohio Statehood Day on March 1, we share six places, artifacts and landmarks that illuminate history and help us see our shared heritage in new ways. READ MORE >>

Spiegel Grove’s Egg Roll Marks 40 Years

The April 4 event at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums commemorates the spring tradition our 19th president brought to the White House in 1878. READ MORE >>