How Lights Out Cleveland Is Helping Save Birds

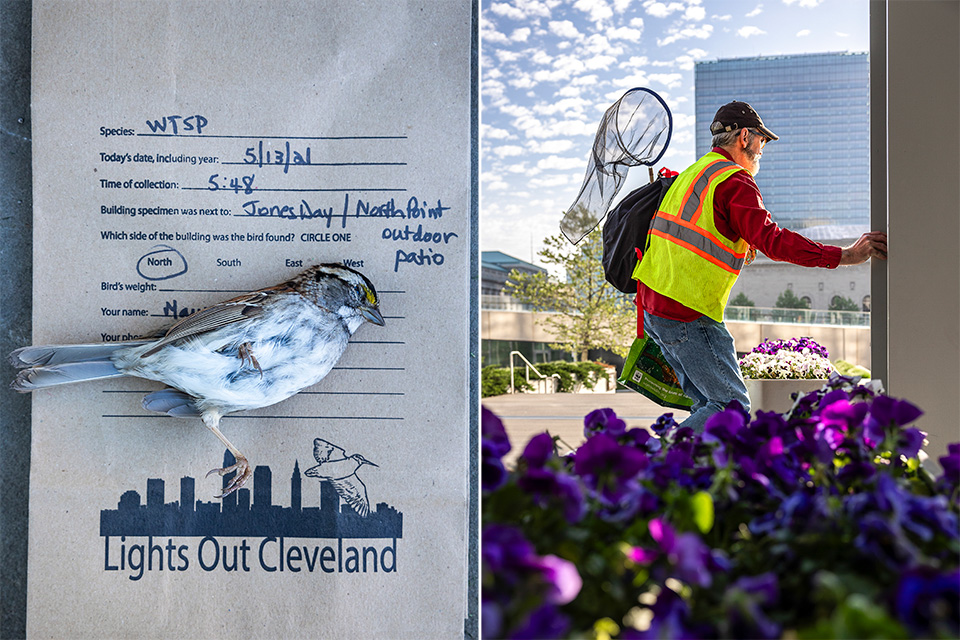

Glowing city skylines are an alluring sight, especially if you're a migrating bird. But an epidemic of collisions with buildings has led groups across Ohio, including Lights Out Cleveland, to form rescue squads and help raise public awareness about the problem.

Related Articles

See the Biggest Week in American Birding at Magee Marsh

With the arrival of May, this northwest Ohio wildlife area becomes one of the best places in the world for bird-watching, thanks to a mix of location, conservation and appreciation. READ MORE >>

Step Inside the Revamped Magee Marsh Visitor Center

The makeover of the former Sportsmen’s Migratory Bird Center provides outdoor lovers a fresh look at our state’s prized bird-watching destination. READ MORE >>

Kenn Kaufman on Taking a Closer Look at Nature

The Oak Harbor resident is an expert in the birding world. We talked with him about the restorative and educational power of spending time outside. READ MORE >>