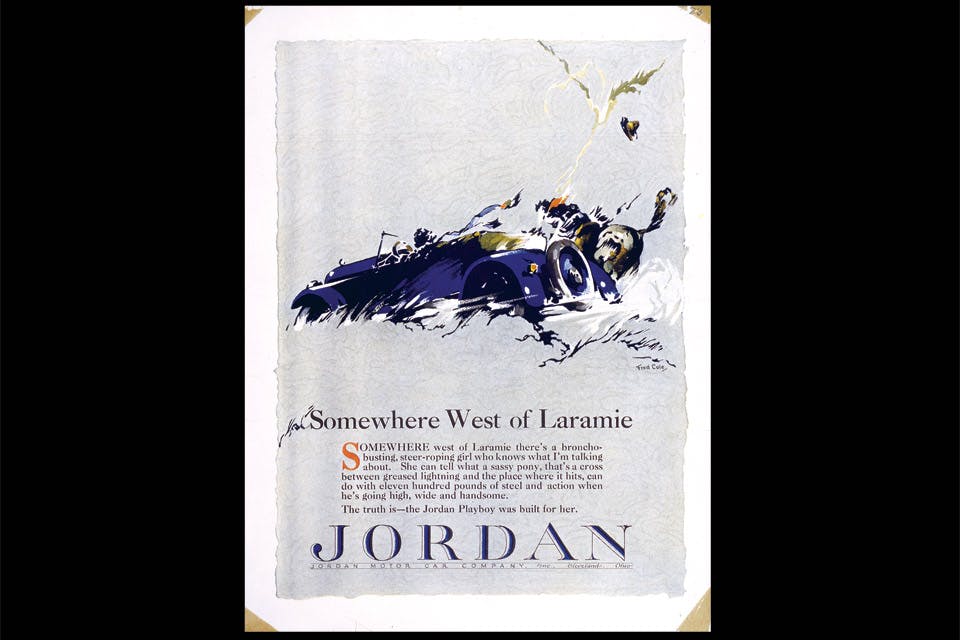

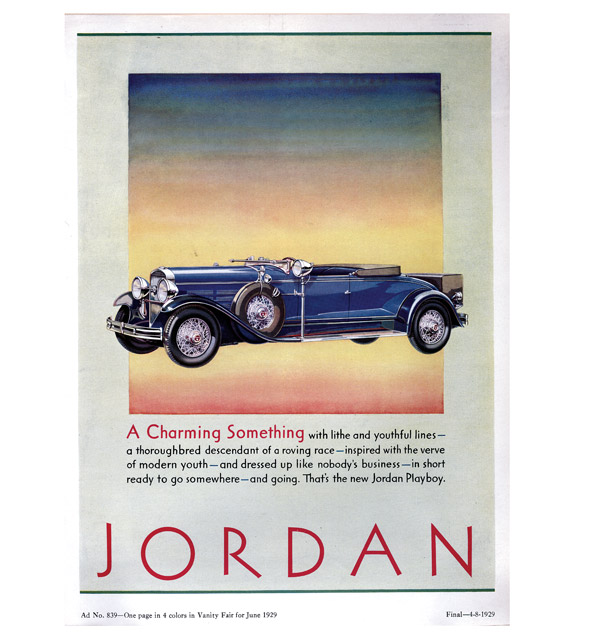

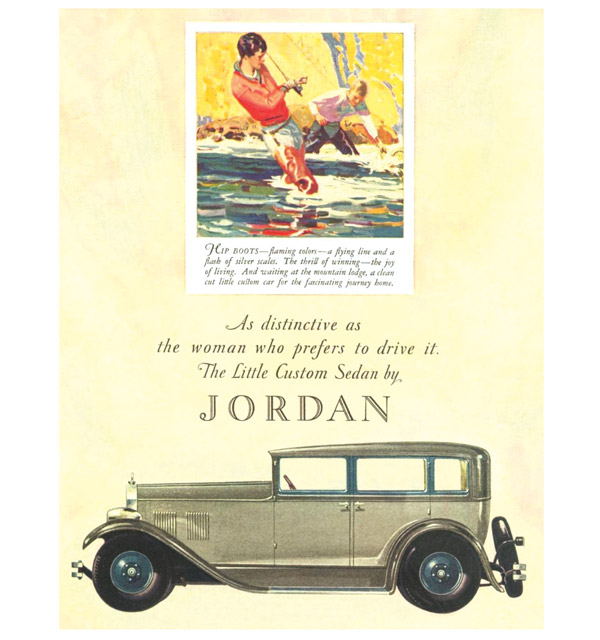

How One Advertisement by the Jordan Motor Car Co. Changed an Industry

Cleveland’s Ned Jordan ran an advertisement in 1923 that forever altered automobile marketing. It didn’t focus on price, engine size or features. It sold a feeling.

Related Articles

_recto.jpg?sfvrsn=c212b438_5&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

How Forgotten Songwriter Ernest Ball Rose to Fame

He isn’t a household name these days, but it’s estimated that the Cleveland native penned over a thousand songs, including Irish-themed standards that are still sung each Saint Patrick’s Day. READ MORE >>

Cold War Discovery Center Opens in Dayton

A new permanent exhibition at Carillon Historical Park examines the city’s rich history in secret research that included work on the atomic bomb. READ MORE >>

See Ohio in a New Way at These Six Historic Sites

In celebration of Ohio Statehood Day on March 1, we share six places, artifacts and landmarks that illuminate history and help us see our shared heritage in new ways. READ MORE >>