Arts

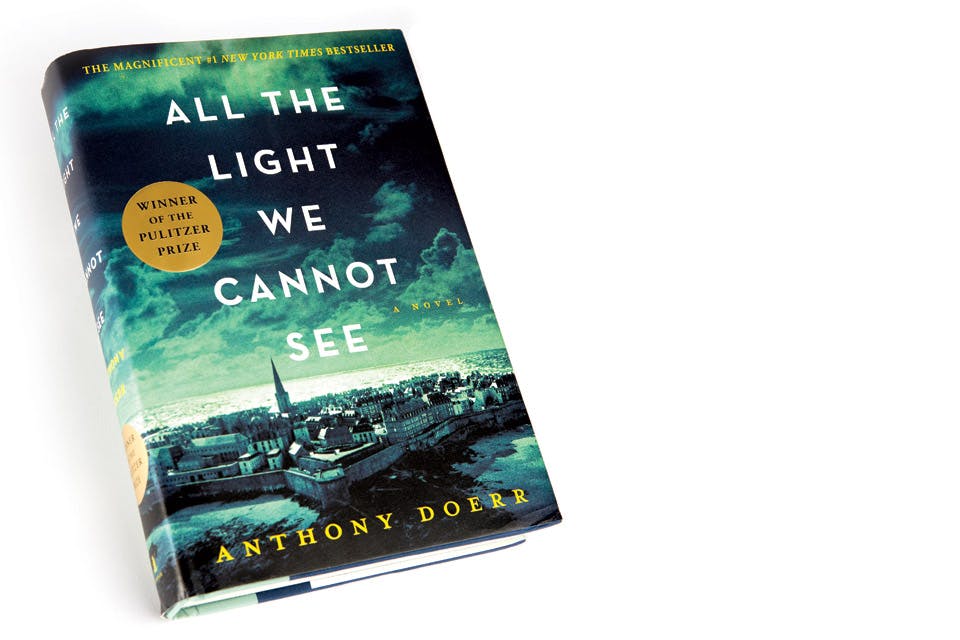

Pulitzer Prize Winner Anthony Doerr Discusses ‘All the Light We Cannot See’

Netflix has adapted the Ohio author’s critically acclaimed book as a limited series. We revisit our 2015conversation with Anthony Doerr about the inspiration for his story

Related Articles

2025 Ohio Book Award Winners Announced

These annual awards from the Ohioana Library honor Ohio-centric books. They will be presented Oct. 15 at the Ohio Statehouse. READ MORE >>

Enjoy Books and Brews at These 3 Ohio Shops

Visit these three Ohio bookstores that go beyond the printed page to offer coffee, beer, wine and more. READ MORE >>

Follow-Up With ’True Raiders‘ Author Brad Ricca

The Cleveland-based author’s new book delves into the details behind a real-life 1909 expedition to find the Ark of the Covenant. READ MORE >>