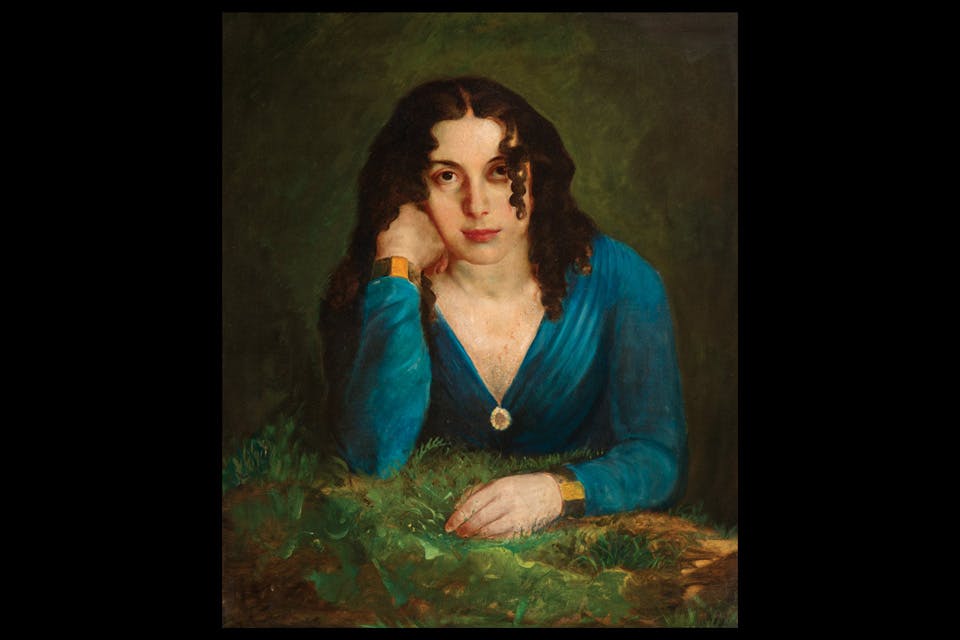

‘Lilly Martin Spencer’ at Decorative Arts Center of Ohio

The Ohio artist supported her husband and 13 children by capturing everyday scenes that spoke to 19th-century, middle-class society.

Related Articles

Cincinnati Writer and Musician Nick Greenberg Talks Fungi Fiction

The classically trained musician in a variety of styles also had a stint in the food industry, which he draws from for his novels that feature culinary capers. READ MORE >>

Lords of the Sound Present ‘The Music of Hans Zimmer’

See this acclaimed Ukrainian symphony perform pieces from the award-winning composer in two Ohio cities this March. READ MORE >>

---credit-stefan-cohen.jpg?sfvrsn=fcd2b438_5&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Apollo’s Fire Presents ‘Winter Sparks’

Cleveland-born group Apollo’s Fire has been delivering electrifying renditions of classical pieces since 1992. This month, the baroque orchestra brings the same intensity to four northeast Ohio performances. READ MORE >>