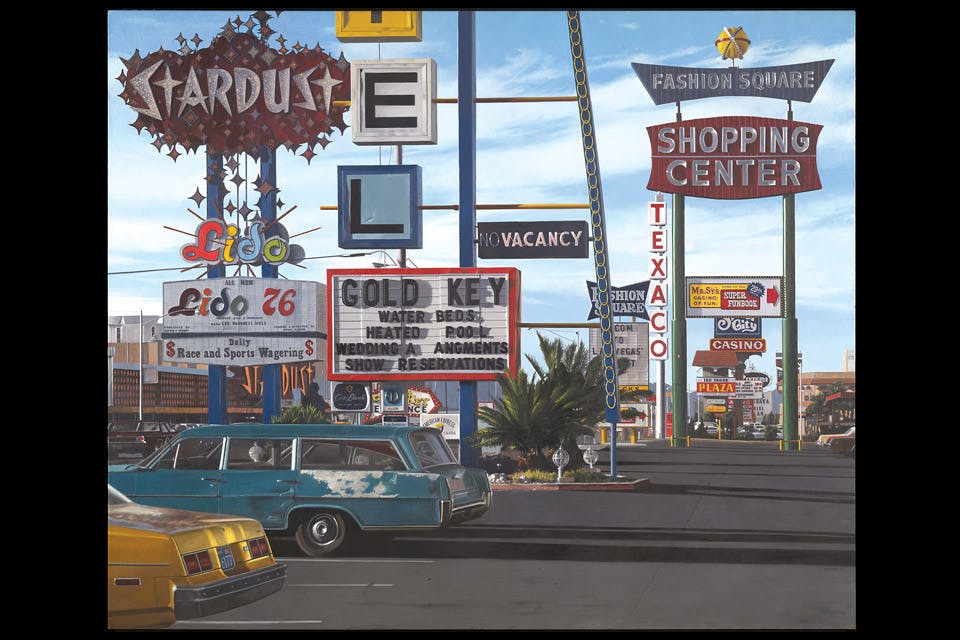

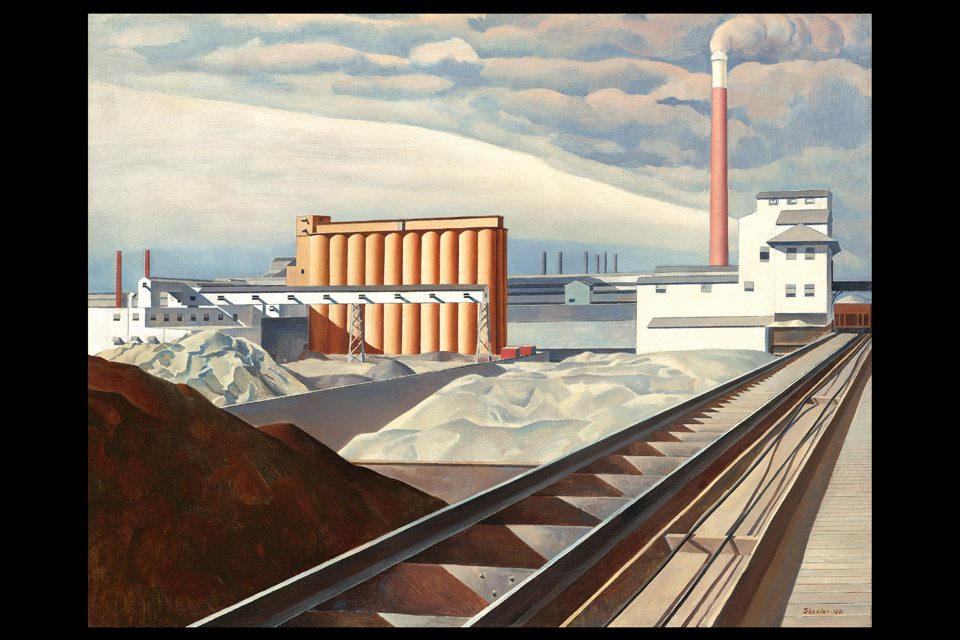

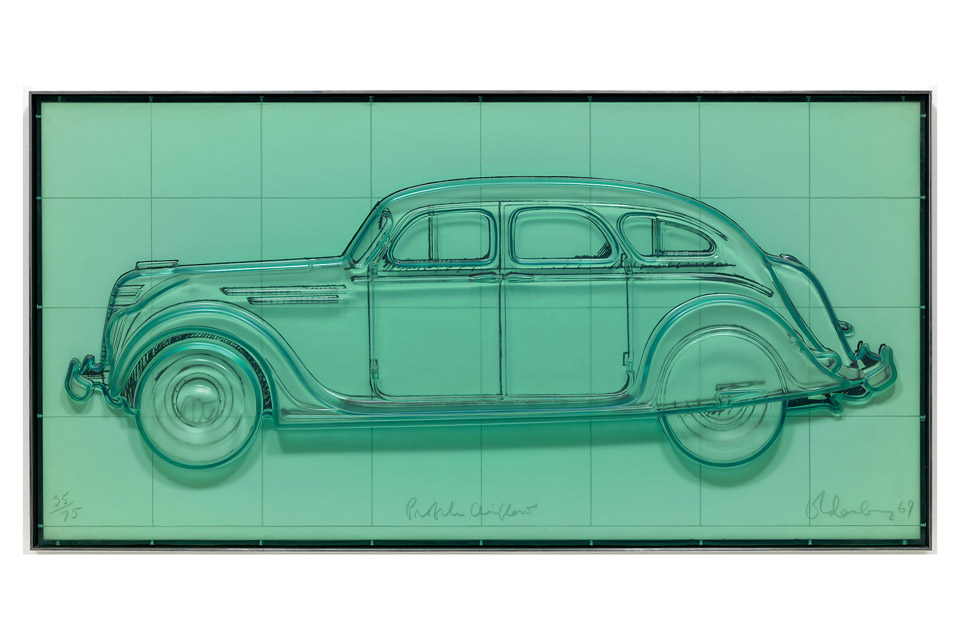

‘Life is a Highway: Art and American Car Culture’

A summer exhibition at the Toledo Museum of Art looks at how the automobile has impacted our lives.

Related Articles

Cincinnati Writer and Musician Nick Greenberg Talks Fungi Fiction

The classically trained musician in a variety of styles also had a stint in the food industry, which he draws from for his novels that feature culinary capers. READ MORE >>

Lords of the Sound Present ‘The Music of Hans Zimmer’

See this acclaimed Ukrainian symphony perform pieces from the award-winning composer in two Ohio cities this March. READ MORE >>

---credit-stefan-cohen.jpg?sfvrsn=fcd2b438_5&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Apollo’s Fire Presents ‘Winter Sparks’

Cleveland-born group Apollo’s Fire has been delivering electrifying renditions of classical pieces since 1992. This month, the baroque orchestra brings the same intensity to four northeast Ohio performances. READ MORE >>