Arts

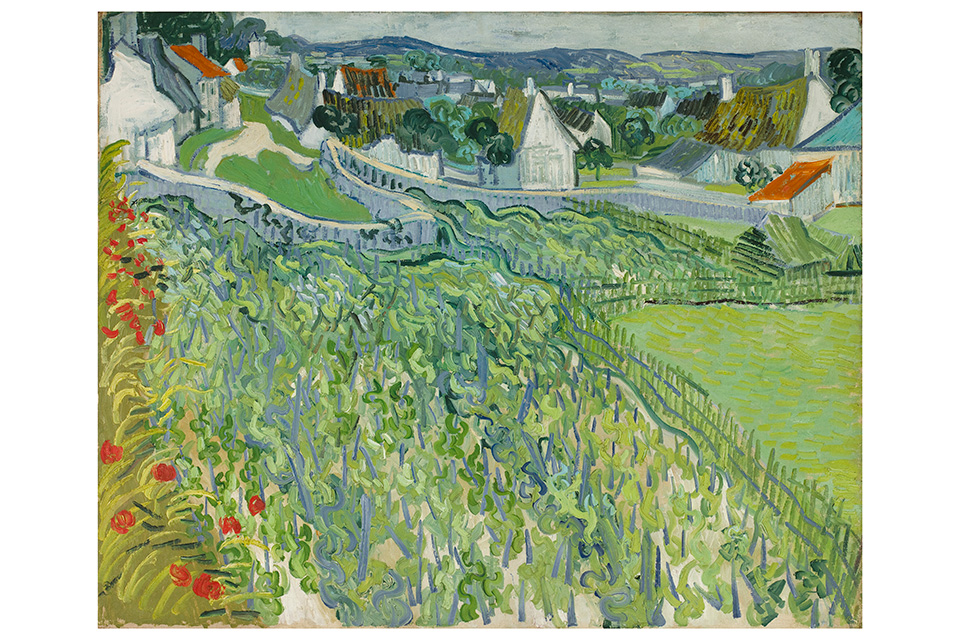

Cincinnati Exhibition Explores Why These Late 1800s French Artists Focused on Food

Discover how art helped reframe France’s national image in the face of war and unrest. “Farm to Table: Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism” runs June 13 through Sept. 21

Related Articles

Lords of the Sound Present ‘The Music of Hans Zimmer’

See this acclaimed Ukrainian symphony perform pieces from the award-winning composer in two Ohio cities this March. READ MORE >>

---credit-stefan-cohen.jpg?sfvrsn=fcd2b438_5&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Apollo’s Fire Presents ‘Winter Sparks’

Cleveland-born group Apollo’s Fire has been delivering electrifying renditions of classical pieces since 1992. This month, the baroque orchestra brings the same intensity to four northeast Ohio performances. READ MORE >>

Concert Posters, Natural History and the Art of Derek Hess

This Cleveland Museum of Natural History exhibition shows how the artist’s concert-poster past evolved into fine art shaped by paleontology, animals and ingenuity. READ MORE >>