Ohio Life

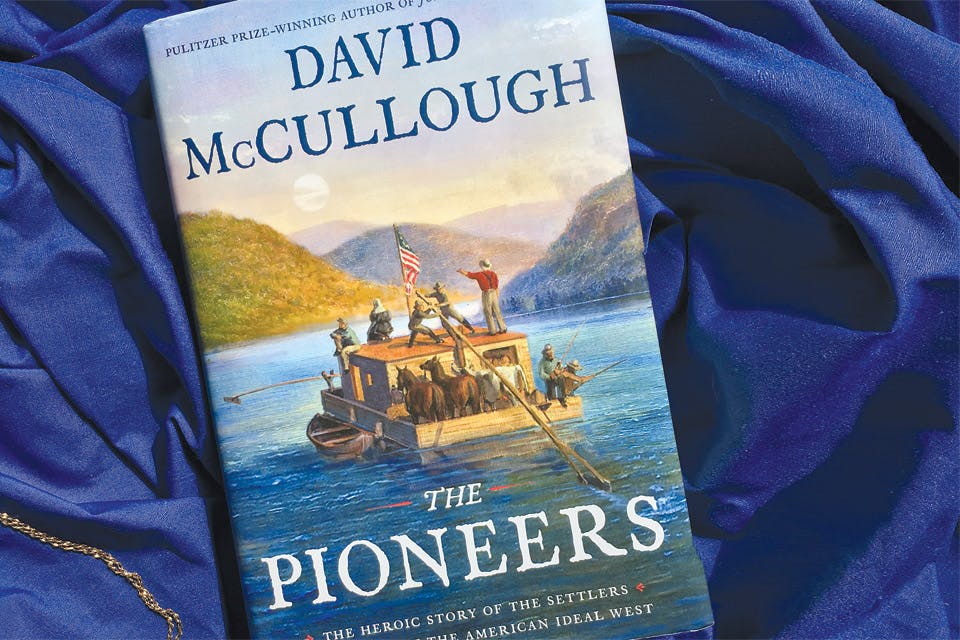

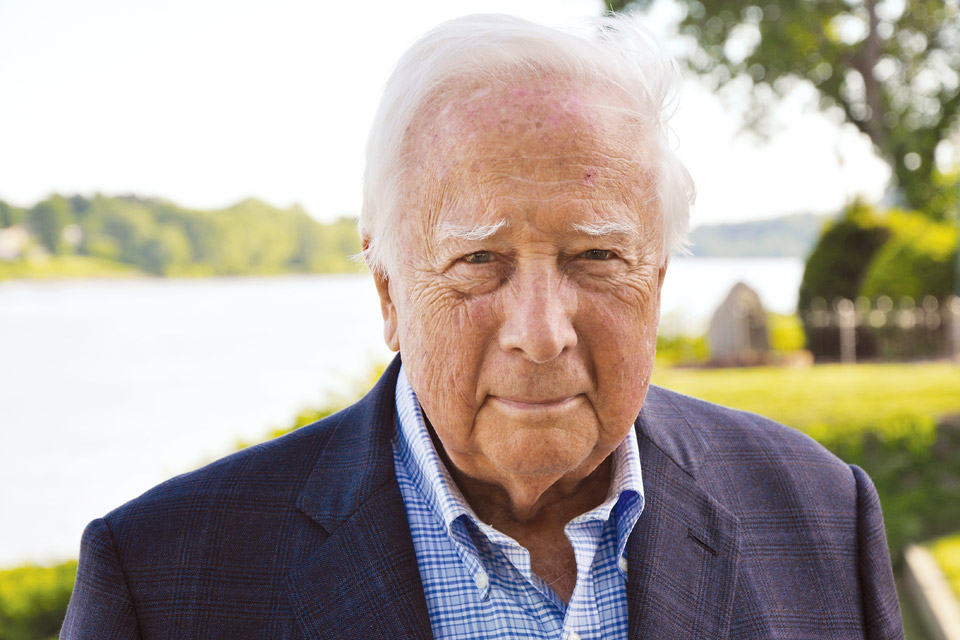

Author David McCullough on ‘The Pioneers’

The Pulitzer Prize-winning historian’s book examines the lives of those who founded Marietta, the United States’ first permanent settlement in the Northwest Territory.

Related Articles

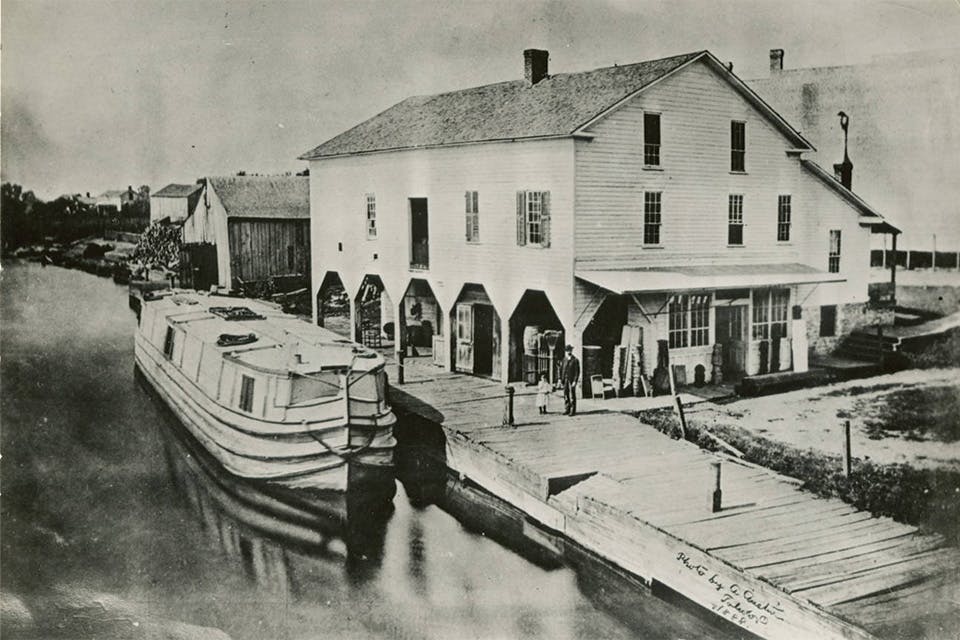

How Ohio’s Canal Era Helped Shape the State’s History

A groundbreaking idea began to take shape in Ohio 200 years ago this summer, as the simultaneous creation of two major canals ultimately opened the state to trade and transformed the place we call home. READ MORE >>

Epworth Park Is One of Ohio’s Last Remaining Chautauqua Communities

This tranquil spot in Bethesda is filled with historic cottages and has a long legacy as a summertime retreat. READ MORE >>

.jpg?sfvrsn=8999b638_5&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Midcentury Barware Show Hosted by Gay Fad Studios Returns to Lancaster

Bottoms Up features gorgeous glassware, entertainment, special presentations and much more over its four-day run. READ MORE >>