How Norman Rockwell’s Boy Scout Paintings Ended Up in Ohio

Iconic American artist Norman Rockwell created 65 Boy Scouts of America paintings. Here’s why they are all on display at a small museum in Trumbull County.

July/August 2020

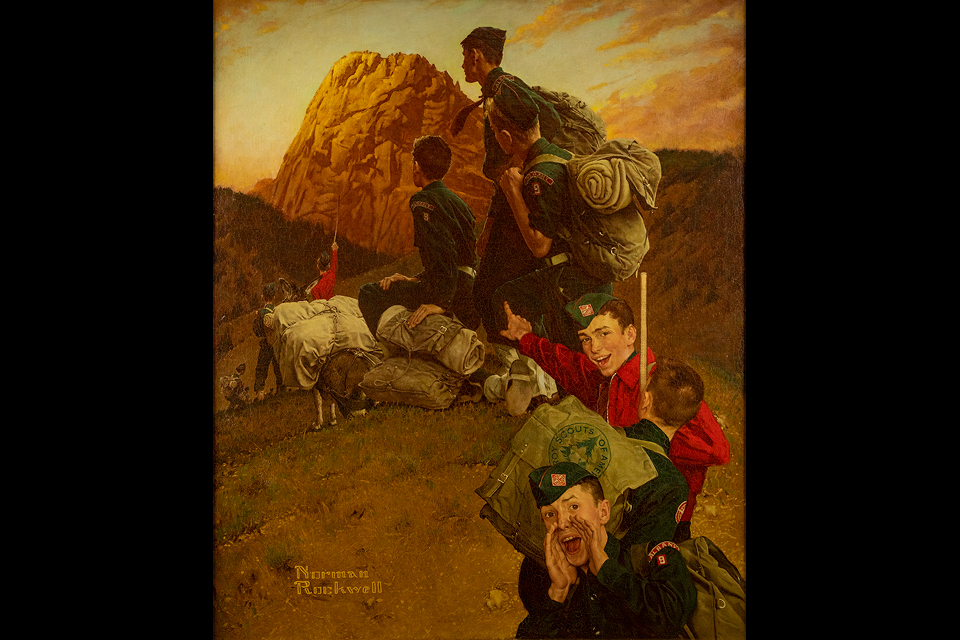

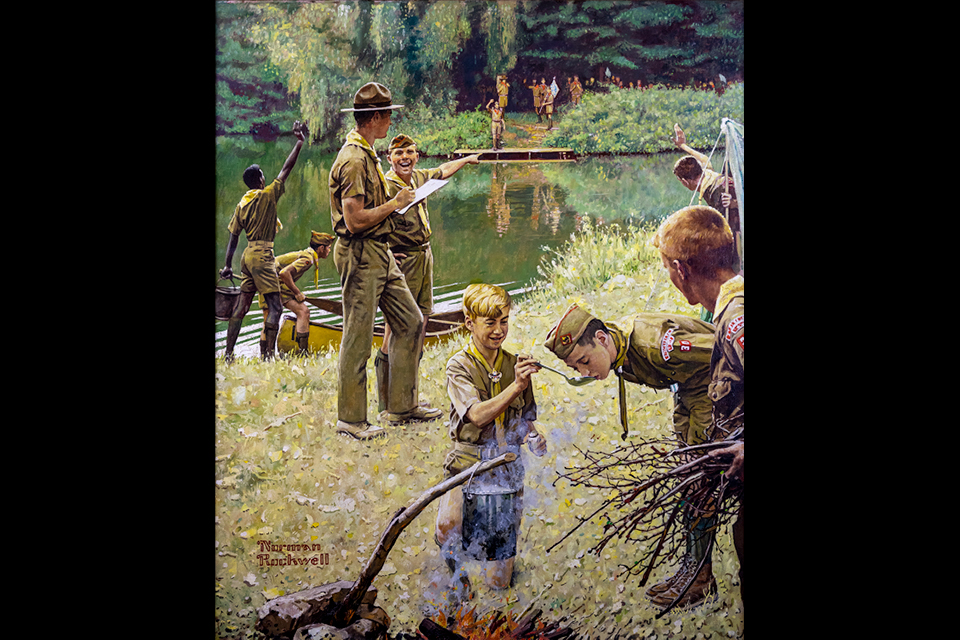

BY Jim Vickers | Norman Rockwell’s “Breakthrough for Freedom” and “America’s Manpower Begins with Boypower” courtesy of the Medici Museum of Art

July/August 2020

BY Jim Vickers | Norman Rockwell’s “Breakthrough for Freedom” and “America’s Manpower Begins with Boypower” courtesy of the Medici Museum of Art

The name Norman Rockwell is synonymous with America. So many of his images have left a mark not only on our culture, but also on us. From 1943’s “Freedom from Want,” in which an elderly couple presents a turkey at the holiday dinner table, to 1964’s “The Problem We All Live With,” depicting a Black 6-year-old girl named Ruby Bridges walking into an all-white public school, Rockwell’s evolution in subject matter traced the progression of our society.

The artist frequently presented an idealized version of the world in which we live, be it the innocence of a young couple at a soda fountain in “After the Prom” or the trio of baseball umpires looking skyward as rain begins to fall in “Tough Call” (also known as “Game Called Because of Rain” and “The Three Umpires”). Rockwell also brought that approach to his paintings of Boy Scouts he made for the cover of Boys’ Life magazine and the organization’s annual calendars. His works depict scouts helping others, learning skills and embracing adventure. Along the way, the artist helped establish the image the Boy Scouts of America embodied for decades.

Today, inside a 10,000-square-foot museum in Trumbull County, Rockwell’s 65 Boy Scout paintings hang in one exhibition — the first time they have all been shown together. How the works ended up on display at the Medici Museum of Art was a circuitous journey led by Ned Gold, a local attorney and a decades-long supporter of the Boy Scouts of America.

Ned Gold, photographed at the Medici Museum of Art in Trumbull County; the institution is the caretaker of the Boy Scouts of America art collection. (photo by Casey Rearick)

The paintings, which are owned by the Boy Scouts of America, were delivered and installed earlier this year, but their future at the museum is far from certain. In February, the Boy Scouts listed the Rockwell paintings in a document it submitted as part of its bankruptcy filing, a response to nearly 1,700 claims from former scouts alleging abuse by troop leaders. Ultimately, a court could order Rockwell’s paintings to be sold. The reality is one Gold prefers not to dwell upon, instead focusing on the positive reactions that the unprecedented exhibition of Rockwell’s works began generating soon after news of their arrival broke.

“The interest from throughout the United States has been phenomenal,” Gold says during a mid-February visit to The Medici. “Locally, every day I get asked, ‘When’s it going to be up?’

***

Even at 79 years old, Ned Gold is all Boy Scout. He grew up in New Mexico, not far from Philmont Scout Ranch, which spans more than 140,000 acres of wilderness in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Owned by the Boy Scouts of America, the ranch opened as a camp in 1938 and was captured in Rockwell’s 1957 painting “High Adventure,” which depicts a line of scouts heading off into the distance as sunlight illuminates the landscape.

“I just love this,” says Gold, as he stands in front of the work. Next to it rests “Tomorrow’s Leader.” It shows a Boy Scout standing in a pose worthy of a classical sculptor with a field of merit badges behind him. Rockwell’s angular and immediately recognizable signature stands out clearly in the bottom right corner of the canvas.

“Look at that — the merit badges, the details,” Gold says with reverence.

The works are two of the 65 Rockwell paintings that arrived at the Medici Museum of Art in February. They are part of a larger Boy Scouts of America art collection that numbers more than 350 pieces. All of the works are housed at the Medici Museum of Art, but “Norman Rockwell: American Scouting Collection” focuses mostly on its namesake. The 65 Rockwell paintings are displayed alongside Boy Scout-themed works from the artist’s predecessor Joseph Christian Leyendecker and his successor Joseph Csatari as well as drawings by Walt Disney. The exhibition was scheduled to open to the public in March, but the coronavirus pandemic delayed its unveiling.

Norman Rockwell’s “High Adventure” depicts scouts at Philmont, the Boy Scouts of America ranch in New Mexico. (artwork courtesy of the Medici Museum of Art)

Gold began chasing the Boy Scouts of America art collection in 2017, after learning the National Scouting Museum was being moved from Irving, Texas, where the Boy Scouts of America is headquartered, to Philmont, but none of the organization’s artworks was going with it.

Due to his longtime involvement with the organization, Gold soon learned that the Boy Scouts were debating whether to sell the art, put it in storage or find a museum where it could be displayed.

“I said, ‘Listen, I got the place for this to go … it’s midway between New York and Chicago, Pittsburgh and Cleveland,’ ” recalls Gold, who had originally worked to secure the collection for The Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, where he was a board member.

After much work, Gold negotiated a deal to bring the collection to Ohio, but there was one hitch: The Butler Institute of American Art’s board of trustees — of which Gold was a member — decided in January 2019 that it would not be accepting the Boy Scouts of America artwork given the controversy surrounding the organization. Instead, the board tabled the issue for one year.

“We’re very proud of our reputation. Could it have been hurt by this? I don’t know. But I think that was certainly a consideration when they decided to table this,” Butler Institute of American Art executive director Louis Zona told Warren’s Tribune Chronicle in a Jan. 25, 2019, article. In the same story, Gold called the decision “incredibly disappointing.”

Former board member John Anderson, the chairman of the Foundation Medici, a nonprofit group that funded the construction of The Butler Institute of American Art’s Trumbull Branch in Howland Township, was also unhappy about the decision. So, he and Gold took another path: Anderson exercised a clause in his agreement to sever his venue’s ties with The Butler and begin working to bring the collection to the newly renamed Medici Museum of Art.

***

It’s a subtle touch, but one you begin to appreciate once it’s pointed out: All of the Boy Scout works displayed on the Medici Museum of Art’s walls are installed about 5 inches lower than works are traditionally presented in a gallery. William Mullane, curator at The Medici, says the decision to show “Norman Rockwell: American Scouting Collection” this way was intentional.

“I realized this show was going to have a number of younger people in the audience,” he explains. “I also realized a lot of our scouting audience is an aged audience, especially ones that were scouts in the ’50s or ’60s.”

Norman Rockwell’s “Tomorrow’s Leader” depicts a scout in a pose worthy of a classical sculptor. (artwork courtesy of the Medici Museum of Art)

The idea is that kids, as well as adults who use wheelchairs, will get a better view of the paintings, while not affecting other museum visitors’ enjoyment. Such intention is infused throughout Mullane’s approach to displaying the exhibition. For one, it is arranged thematically rather than chronologically. The approach highlights the topics that Rockwell embraced in his Boy Scout paintings and how they evolved. He created works for the organization’s annual calendar starting in 1925 (after serving as art director for Boys’ Life magazine at the young age of 19) and revisited the topic of scouting throughout his career.

“I wanted people to get a sense of the recurring themes in scouting, but also how Rockwell handled them over time,” Mullane says. “Because when you go into any particular theme, you’re seeing paintings from sometimes a 20- or 30-year timespan.”

Museum visitors are greeted by a painting of a waving Boy Scout, which once graced the cover of the Boy Scout Handbook. The exhibition starts on the left side of the gallery with “Ever Onward,” which Rockwell painted in 1960 to celebrate scouting’s 50th anniversary. It is a good starting point because it features a dominant theme in the artist’s work: the use of insignias, badges and other visual iconography of the Boy Scouts to illustrate the progression from Cub Scout to Eagle Scout — the journey from boy to young man.

Norman Rockwell’s “Come and Get It” is among the 65 Boy Scouts of America paintings on display at the Medici Museum of Art. (artwork courtesy of the Medici Museum of Art)

From there, the exhibition moves on to the theme of the family’s relationship to scouting, including the works “Mighty Proud” and “Homecoming.” The former, created in 1961, shows a young Boy Scout putting on his new uniform, while the latter — a piece Rockwell painted for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in 1945 — depicts a family welcoming their Boy Scout home from camp. Rockwell’s compositions from this era seem dated now, given their focus on all white families.

“Illustration in the ’50s and ’60s is really reflective of what the publications wanted and would accept,” Mullane says. “So, when you look at illustration in general and you look at it chronologically, shifting tastes, shifting beliefs and shifting sensibilities are reflected in illustration and advertising.”

Other themes covered in the exhibition include honor, the National Jamboree, historic images, reverence, adventure, helping others, learning from adults, the scoutmaster as leader, and teacher and group portraits.

Rockwell’s works did evolve to include minority scouts. His “Breakthrough for Freedom” in 1967 shows six scouts of different nationalities walking arm in arm. His 1971 painting “America’s Manpower Begins with Boypower” depicts two Cub Scouts — one Black, one white — standing beside their den mother with older scouts in the background.

“What’s important to the Boy Scout genre, is throughout all that time, a shift takes place culturally,” Mullane says, “but the ideals that are visited [in the works] — honor, family, reverence, leadership and learning — don’t.”

***

In June, the Boy Scouts of America awarded its Silver Buffalo Award to Ned Gold, one of 14 people to receive scouting’s highest volunteer honor this year. He was recognized for his involvement in founding and organizing the Philmont Staff Association, which has raised millions of dollars for the ranch over the past 47 years. But this year’s virtual awards ceremony also noted Gold’s role in getting Rockwell’s famous paintings out of storage and put on public display.

Norman Rockwell’s “Mighty Proud” shows the role scouting played in the American family. It also illustrates the artist’s flair for storytelling in the small details. (artwork courtesy of the Medici Museum of Art)

“All you have to do is look around at all the Norman Rockwell scout paintings,” Gold offered in his recorded remarks to his fellow recipients. “This tells the story of why everybody stays in scouting, and I hope everyone gets here to see the whole collection.”

In early June, the Medici Museum of Art reopened by appointment for groups of 10 or fewer. “Norman Rockwell: American Scouting Collection” will be on display in its current form until at least November, when a scheduled expansion to the museum will open additional gallery space to display other pieces from the scouting collection. But the Rockwell paintings are the ones that promise to connect visitors across generations.

“Those of us who have been in scouting and have been very deeply involved in the program, we’ve all grown up with the Rockwell paintings,” Gold says.

Although the fate of the collection is unclear given the Boy Scouts of America’s legal problems and the value of Rockwell’s paintings, the works will reside at the Medici Museum of Art for the foreseeable future. Gold negotiated an agreement that the works won’t be sent to another museum or back to storage as long as conditions regarding their care and promotion are met.

For Gold, bringing such an incredible body of work to light has been deeply satisfying, especially because any time he had seen more than one of Rockwell’s original Boy Scout paintings on display over the years, he’d always been left wanting more.

“I was always disappointed that they only ever had six or seven, eight or nine Rockwells up at one time,” Gold says of his previous visits to the National Scouting Museum. “I never believed I was going to the be the one who put them all up in one place for the first and probably the last time.” For more information, visit medicimuseum.art.

Related Articles

Concert Posters, Natural History and the Art of Derek Hess

This Cleveland Museum of Natural History exhibition shows how the artist’s concert-poster past evolved into fine art shaped by paleontology, animals and ingenuity. READ MORE >>

Every Exhibition at the Dayton Art Institute in 2026

From traveling shows featuring the works of artist Tony Foster and William H. Johnson to focus exhibitions curated from the museum’s collection, here is what’s on the schedule this year. READ MORE >>

New Immersive Augmented Reality Experience Coming to COSI

Starting Jan. 30, visitors to the Columbus science destination can explore and interact with imaginary, virtual worlds through this holographic theater exhibit. READ MORE >>