Ohio Life

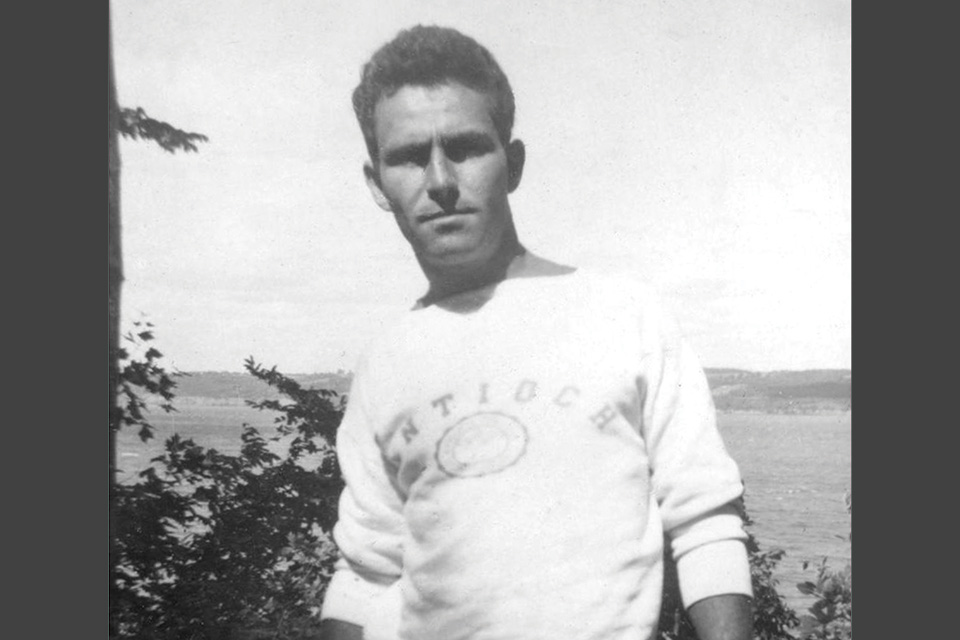

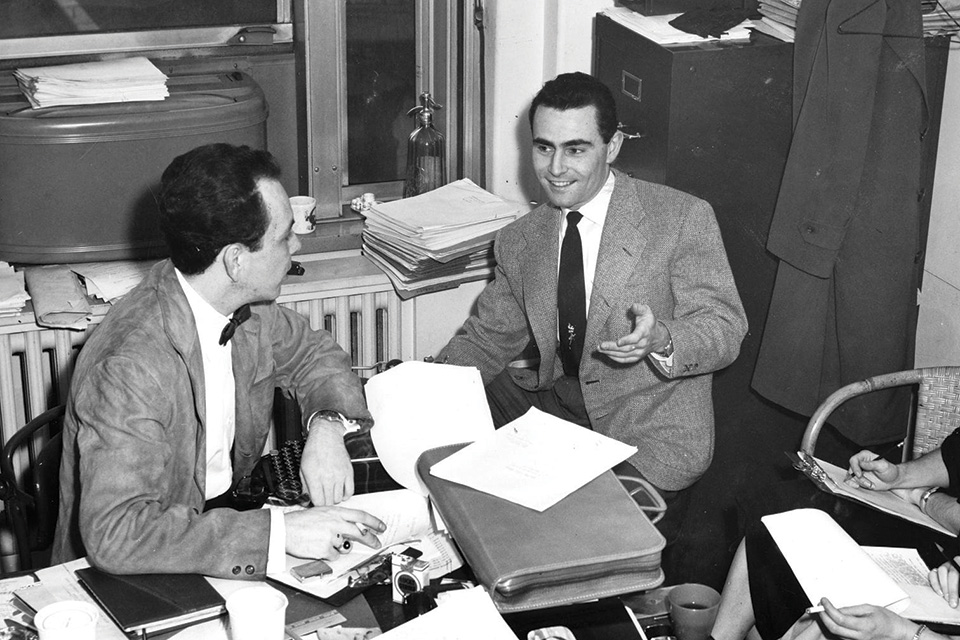

How Ohio Shaped Rod Serling’s ‘The Twilight Zone’

Rod Serling created his iconic television series after spending time in Ohio writing radio and television dramas that examined themes of human nature, morality and society’s deepest anxieties.

Related Articles

Ohioan Emma Betsinger Talks ‘Love Is Blind’ Season 10

The new season of the Netflix series, which debuted Feb. 11, features Ohioans looking for love. Columbus-based contestant Emma Betsinger talked with us about her experience. READ MORE >>

.jpg?sfvrsn=21d9b438_3&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Discover 3 Newly Recognized Underground Railroad Sites in Appalachian Ohio

The National Park Service has recently acknowledged three Ohio communities that played a role in helping Civil War-era freedom seekers. READ MORE >>

Learn the Sweet History of The Dawes Arboretum at Maple Syrup Day

The Newark arboretum’s founders, Beman and Bertie Dawes, began harvesting sap for maple sugar in 1919. Today, the annual Maple Syrup Day shares that heritage with visitors. READ MORE >>