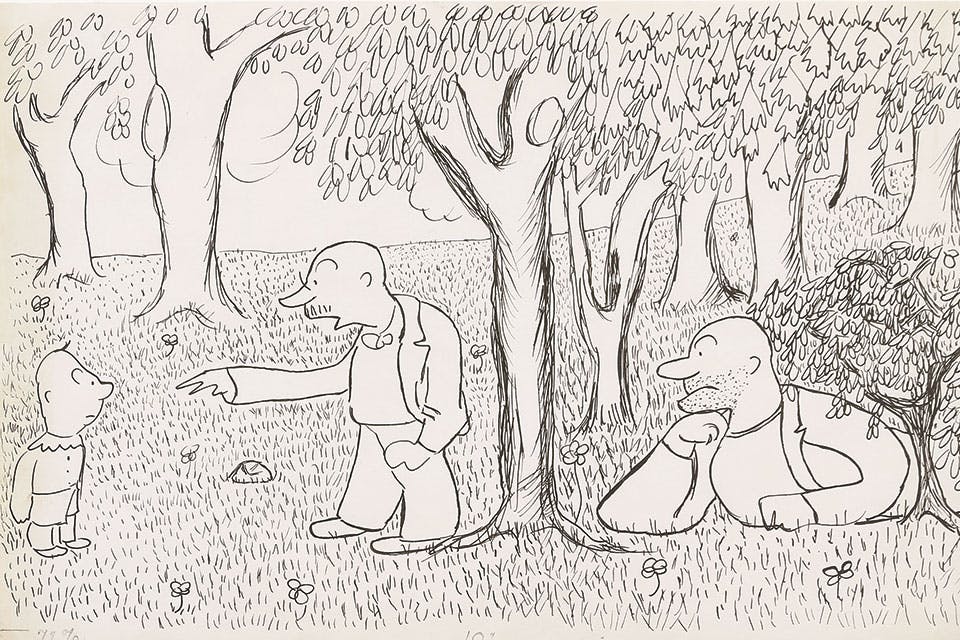

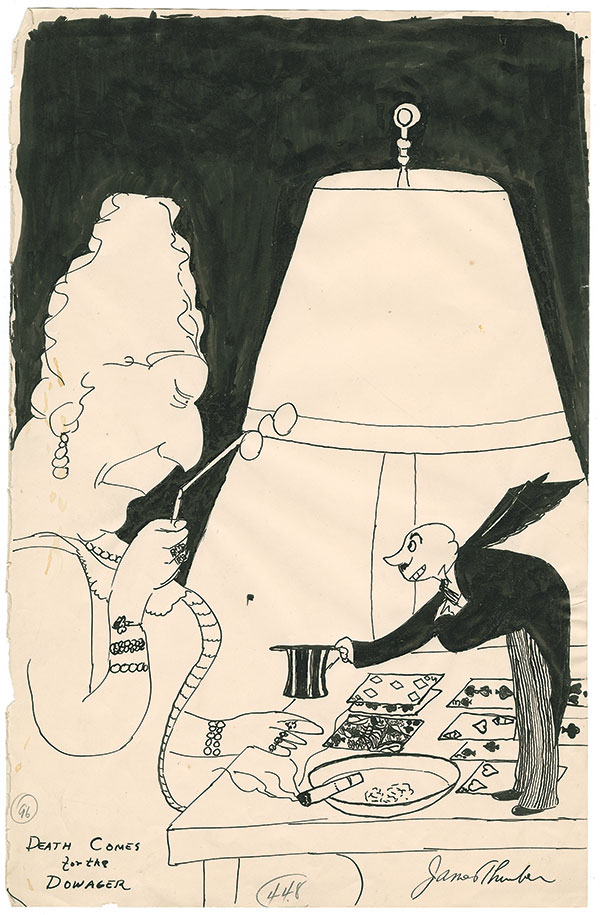

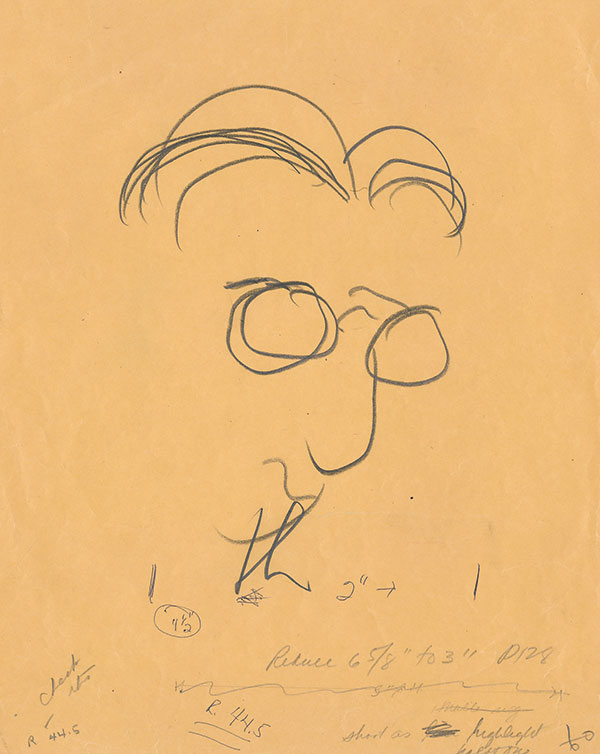

‘A Mile and a Half of Lines: The Art of James Thurber’

A Columbus Museum of Art exhibition examines how native son James Thurber changed the face of American cartooning during the first half of the 20th century.

Related Articles

See the World’s Largest Collection of Lithophanes at this Ohio Museum

The Blair Museum of Lithophanes at the Schedel Arboretum & Gardens in Elmore is dedicated to the 19th-century art form, housing more than 2,300 unique pieces. READ MORE >>

Concert Posters, Natural History and the Art of Derek Hess

This Cleveland Museum of Natural History exhibition shows how the artist’s concert-poster past evolved into fine art shaped by paleontology, animals and ingenuity. READ MORE >>

Every Exhibition at the Dayton Art Institute in 2026

From traveling shows featuring the works of artist Tony Foster and William H. Johnson to focus exhibitions curated from the museum’s collection, here is what’s on the schedule this year. READ MORE >>