Toni Morrison’s Journey to Becoming a Literary Icon Began in Ohio

As a child growing up near the steel mills of Lorain, Toni Morrison, Nobel laureate from the “lip of Lake Erie,” learned to love — and tell — a great tale.

August 2019

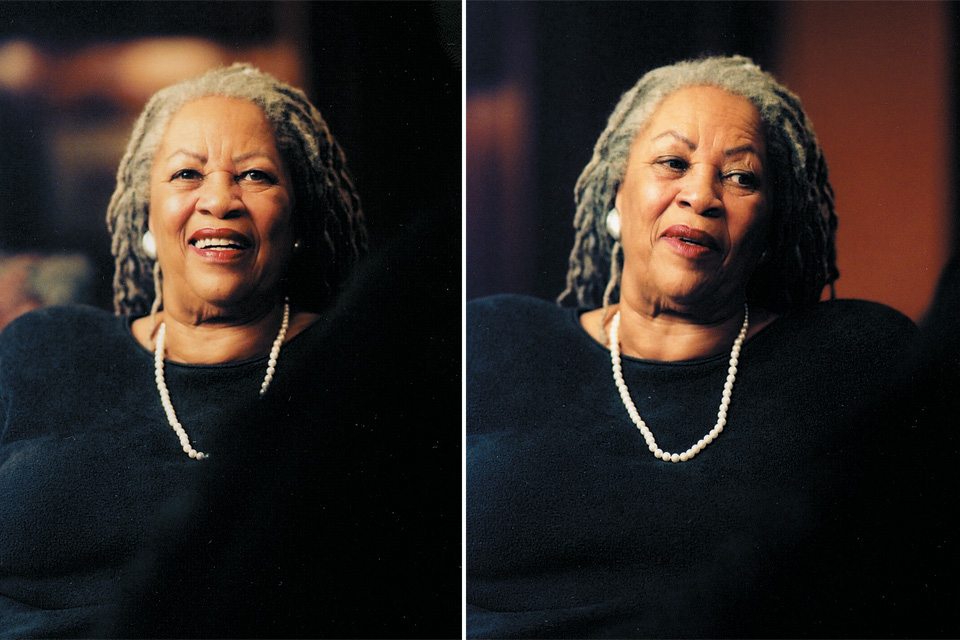

BY Jennifer Haliburton | Photo by Jerry Mann

August 2019

BY Jennifer Haliburton | Photo by Jerry Mann

Editor’s Note: In 2003, staff writer Jennifer Haliburton interviewed Toni Morrison about her time growing up in Lorain, Ohio, and how it shaped her life and her work. The resulting story originally ran in the November 2003 issue of Ohio Magazine.

The story of the little girl from Lorain could have been just another one of Ella Wofford’s tall tales.

Ella was, after all, a masterful storyteller, capable of summoning magical plot lines and exotic characters on a moment’s notice to entertain her two daughters on chilly autumn nights. Sitting in their usual seats near the warm, pot-bellied stove, the girls would have been spellbound as Ella unwound the story of the Lorain girl named Chloe, a poverty-stricken child from a small steel town who grows up to achieve great fame and fortune. Ella would have described how Chloe’s family endured terribly difficult times during the Great Depression — how when they could no longer afford the $4-a-month rent, their vindictive landlord set the family’s house on fire — and her daughter would have gasped in horror. The girls would imagine little Chloe crying, her family embracing each other on the sidewalk in front of their burning home, watching in disbelief as flames and thick smoke poured from the windows and turned the gray Lorain sky even darker.

Ella’s daughter reveled in her stories. Whenever she told the tale of Cinderella, reciting how the beautiful servant girl waltzed with a prince at a glamorous ball, the youngest daughter would rise from her seat and dance around the room.

Young Toni Morrison — born Chloe Wofford — spinning around the room as her mother spun fantasy and folklore, didn’t know that her own life’s story would one day rival Ella’s tales. As she glided across the room, the story of Cinderella providing the soundtrack to her dancing, Morrison didn’t know that she could be preparing for the day in 1992 when she would attend a sort of magical ball of her own at the Grand Hall in Stockholm, Sweden. The day when she — already the star of the ceremony as the first African-American to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature — would mirror a character in one of Ella’s fair tales, as the sequins on her long, black gown began reflecting the Grand Hall’s 13 chandeliers and making Morrison shine like a beacon.

The scene was a long way from the smokestacks and steel mills of Lorain that were the backdrop of Morrison’s youth in the 1930s and ‘40s. But her work that was honored by the Swedish Academy — and has made her an international best-selling author and a Pulitzer Prize winner, earning her the title of “America’s greatest storyteller” by Time magazine pulses with the images, impressions and ear for dialogue she cultivated while growing up in Ohio.

“There are a lot of people from Ohio in publishing in New York,” says Morrison, 72, who is promoting Who’s Got Game? The Lion or the Mouse?, the latest in a series of children’s books she has co-authored with her son, Slade, as well as her seventh novel, Love, to be released this month. “They speak about their Ohio towns with … complete contempt, as though they had been in a prison. It was someplace that they just had to leave. But I don’t feel that way about the town I was born in. … I don’t mean it was all happy, but it was unique for me. I never felt as though I was running away from it.”

“The town you’re born in is either in your blood or it’s not,” says author Toni Morrison. “I always liked that [Lorain] was a working-class town.” (photo by Jerry Mann)

Morrison has written that, “Ohio offers an escape from stereotyped black settings. It is neither plantation nor ghetto.” Lorain was in the grips of the Great Depression when Morrison was born in her grandparents’ home on Elyria Avenue on Feb. 8, 1931 — the second of four children. However, in previous years, the town had not only offered an escape for African-Americans seeking refuge from the brutal prejudice of the South, it was also a haven for European immigrants hoping to find financial stability in the town’s many industrial plants. Once an agricultural town, Lorain found itself in the perfect location to benefit from the country’s booming production of steel in the early 20th century: the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad ran through town, conveniently connecting Lorain to coal deposits in the southern parts of the state; the Nickel Plate Railroad tied it to major hubs of commerce, including Chicago and New York City; and the town sat nicely on the spot where the Black River meets Lake Erie — prime territory for shipbuilding.

The geography was too attractive for industry to ignore. Thew Shovel Company set up shop in south Lorain along the B&O tracks. East Lorain offered the best spot for The American Shipbuilding Company. Then, of course, there was the king of them all, The National Tube Company, which moved to Lorain in 1894, its network of blast furnaces and rail bar and pipe mills quickly consuming one-fifth of the town and luring 9,000 laborers at its peak in the early 1920s.

"There were so many people working in the plants and the shipyards — there was always a lot of labor here," recalls Morrison. It was this often-gritty landscape of factories and freighters that provided the setting for Morrison’s first book, 1970’s The Bluest Eye — the only one of her works to feature her hometown. The story follows two sisters and their friendship with 11-year-old Pecola Breedlove, a girl who believes everyone would love her — including the mother who neglects her, the father who victimized her, and the society that shuns her — if only she had blue eyes. Morrison filled the book with Lorain references — alternating the names of some places as when she refers to Lorain’s Zipp’s Coal Company as “Zick’s.” In The Bluest Eye, the sisters, Claudia and Frieda, traverse the town, a setting as unwelcoming as Pecola’s family:

Grown-ups talk in tired, edgy voices about Zick’s Coal Company and take us along in the evening to the railroad tracks where we fill burlap sacks with the tiny pieces of coal lying about. Later we walk home, glancing back to see the great carloads of slag being dumped, red hot and smoking, into the ravine that skirts the steel mill. The dying fire lights the sky with a dull orange glow. Frieda and I lag behind, staring at the patch of color surrounded by the black. It is impossible not to feel a shiver when our feet leave the gravel path and sink into the dead grass in the field.

With companies based on steel production quickly making Lorain home, so did a mix of European immigrants and laborers from across the country. The National Tube workforce was so diverse signs in the company’s mills were often printed in five or six different languages. The population would eventually be made up of residents from such a wide range of countries, Lorain could be coined “the International City.”

***

“A real melting pot is what they used to call it, and it was,” says Morrison. She remembers that, unlike the biting racism and sharply drawn color lines that existed in many small towns in America in the early 20th century, Lorain’s unique cultural diversity had Irish people living next to Portuguese people living next to African-Americans living next to whites. And during the Depression, when steel production slowed dramatically and National Tube reduced its workforce from 9,000 to only 1,300 full-time workers in 1932, these families who all shared the same employers were all equally poor.

“I think people in many parts of the country are not familiar with the ways in which small, industrial towns work; they have this stereotyped impression of how things are between the races,” says Morrison, who, while living on 21st Street, fashioned dolls out of toothpicks and hollyhock flowers with her Italian and German neighbors. “When I grew up, the major differences between people were not racial, they were financial.”

“There wasn’t that much middle class here — you either had money or you didn’t,” says Morrison’s sister, Louis Brooks. The girls and their two brothers felt the sting of the Depression when they were forced to move into nearly a dozen different houses and storefronts in Lorain in the 1930s and ’40s. Like many blacks migrating to the area, Morrison’s parents, George and Ella Ramah Wofford, both the children of Southern sharecroppers, had come seeking opportunities for employment and education the South refused to offer. But during the worst years of the Depression, the family faced poverty, and Morrison’s father struggled to make ends meet as a welder in the steel mill and as a construction worker, and in whatever other jobs he could find.

Toni Morrison was inspired by the works of authors ranging from Tolstoy to Faulkner at the Lorain Public Library. In 1995, the library dedicated the Toni Morrison Reading Room in her honor. (photo by Jerry Mann)

Although Morrison has no recollection of the landlord setting the Wofford home on fire, she recalls her mother reciting the story with a mix of “anger and amusement.”

“The rent was $4 a month!” says Morrison, laughing at the sum that seems so meager now. “People have no concept of the level of poverty that existed during the Depression.”

Although the common economic hardship in Lorain erased some of the racial conflict that was so prevalent in other towns of the era, Morrison’s sister notes that “segregation was here … but it was more subtle, which can sometimes really be meaner than those kinds that people are upfront with.”

Morrison addressed the issue in The Bluest Eye, referencing Lakeview Park (“Lake Shore Park” in the book) — an area that was off-limits to Morrison and other blacks in Lorain:

We reached Lake Shore Park, a city park laid out with rosebuds, fountains, bowling greens, picnic tables. It was empty now, but sweetly expectant of clean, white, well-behaved children and parents who would play there above the lake in summer before half-running, half-stumbling down the slope to the welcoming water. Black people were not allowed in the park, and so it filled our dreams.

In the midst of the economic turmoil and subtle segregation, a number of people in Lorain infused Morrison with the inspiration, encouragement and sense of curiosity that would lead the future author to write seven novels. The first was her mother, Ella.

“I was reading at three or four [years old],” recalls Morrison, who was the only member of her kindergarten class who knew how to read upon entering school, and was often placed next to immigrant children in her classes to aid them in reading. While her father worked the steel mills, Ella cared for the children at home, reciting poetry, supplying them with books telling folklore and instilling in the young Morrison the cadence and style of a gifted storyteller.

“My mother was very good at that,” says Brooks, 74, recalling the tales her mother would either recite from memory — such as a ghost story passed down for generations — or one concocted on the spot. “It was mostly folklore; you won’t find them written down anywhere,” she says. “It would usually [take place] in the evening, especially [in autumn]; I remember our father would be out on the farm picking apples. We would sit around this pot-bellied stove and she would tell stories. It was the same way down at our grandmother’s house.”

While Morrison learned the fundamentals of storytelling at home, she was also inspired by the works of everyone from Tolstoy to Faulkner at the Lorain Public Library.

“It was very much an important part of my life,” recalls Morrison, who worked as a library aide there as a teenager. “Whether I worked there or not, I was always there — it was where all the books were.” Morrison and Brooks, a secretary to the head librarian, often found themselves spending long hours in the library reading whole aisles of fiction, and the nurturing staff there took pride in the girls’ reading, selecting books and engaging them in discussions on the characters.

It was in recognition of this supportive environment that Morrison, learning that Lorain was planning to honor her in some way, suggested creating a reading room at the library. “It sounds ordinary, but libraries have become very complicated places, with computers and CDs and children’s hours — they’re very busy now,” she says. “I wanted [the reading room] to be the kind of place where people could just drop in, sit down and read books.”

The Toni Morrison Reading Room was opened at the Lorain Public Library on Sixth Street in 1995. The library attempts to collect all books written by and about Morrison, and the Reading Room, decorated with oak display cases and bookshelves, contains a wealth of Morrison memorabilia, including autographed works, article reprints and photographs. The speech she gave at the Nobel Prize ceremonies is etched in glass at the room’s entrance.

The room was just one stop on a tour that was part of the Toni Morrison Society’s Second Biennial Conference last year. More than 1,000 people, including scholars from as far away as Japan and Brazil, gathered in Lorain for three days of workshops and discussions of Morrison’s work.

“There was a person from Germany here, and he said ‘Lorain should be like Stratford-on-Avon! It should be that famous!” says Marilyn Valentino, literature professor at Lorain County Community College, director of the 2002 conference and charter member of the society, which has nearly 400 members worldwide.

Valentino arranged for school buses to take 300 of the attendees to a number of Lorain sites where Morrison spent her childhood and that were immortalized in print in The Bluest Eye.

“They saw all these places that were mentioned in the book and where she grew up, and it was like going down to Faulkner’s Mississippi,” says Valentino. “When we stopped at the house on Elyria Avenue where she was born, they all got out and took pictures.”

After Morrison graduated with honors from Lorain High School in 1949, she moved to Washington, D.C., to attend Howard University — “to be around black intellectuals,” she explains. It was there that she acquired the nickname Toni, and before long, recalled the landscape of Lorain for The Bluest Eye.

A string of accomplishments followed. Her third novel, Song of Solomon, received the National Book Critics Circle Award and the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters Award in 1977. She appeared on the cover of Newsweek in 1981 after Tar Baby was published — the first black woman to be featured on the cover of a national magazine since author Zora Neale Hurston in 1943. And she won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for Beloved in 1988, a novel that was made into a film by Oprah Winfrey in 1998.

Morrison, who holds a B.A. in English from Howard and an M.A. from Cornell University, also writes nonfiction and holds a number of prominent teaching positions, including her appointment in 1989 as the Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities at Princeton University — the first African-American woman to have an endowed chair at an Ivy League college.

But despite her successes and international acclaim, Morrison still carries the memories of her home and her hometown, which she told a crowd in a speech at Oberlin College in 1991, manage to weave their way into everything she does.

“In my work, no matter where it’s set — New York, Martinique, wherever — the process, the imaginative process, always starts right here on the lip of Lake Erie.”

Related Articles

Follow-Up With ’True Raiders‘ Author Brad Ricca

The Cleveland-based author’s new book delves into the details behind a real-life 1909 expedition to find the Ark of the Covenant. READ MORE >>

Ohio Literary Trail

This book lover’s road trip includes the family home of the woman who helped change Americans’ views on slavery and a museum celebrating the art of the picture book. READ MORE >>

Connie Schultz on ‘The Daughters of Erietown’

The author and Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist’s debut novel delves into the dreams and realities of working-class families. READ MORE >>