Arts

Artistic Blueprint

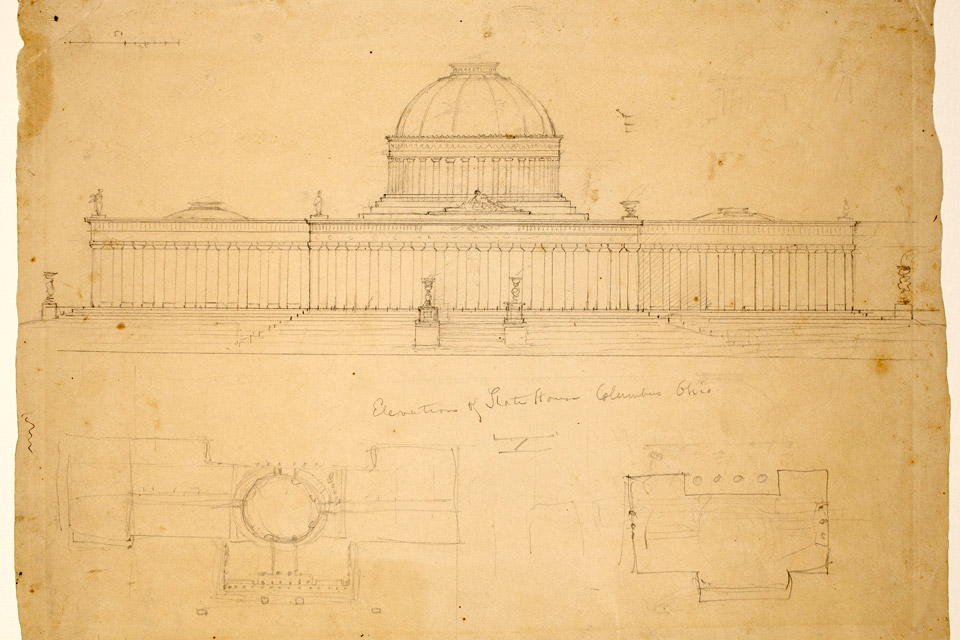

The Columbus Museum of Art highlights works by Thomas Cole, a painter who went on to become one of the architects of the Ohio Statehouse.

Related Articles

See “Monet in Focus” at the Cleveland Museum of Art

This exhibition features five paintings by renowned French impressionist painter Claude Monet that show the various ways he captured light and atmosphere in his work. READ MORE >>

See ‘Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined in Glass’ in Cincinnati

Featuring works by 33 contemporary artists, this insightful exhibition is on display at the Cincinnati Art Museum through April 7. READ MORE >>

Drelyse African Restaurant, Columbus

Restaurateur Lisa Bannerman’s capital-city spot serves the authentic dishes she grew up with in Ghana. READ MORE >>