4 Amish Families who Welcome Visitors Inside

Experience the old ways with four Amish families who open their homes and lives to curious visitors.

September 2015 Issue

BY Linda Feagler | Illustrations by Jeff Suntala

September 2015 Issue

BY Linda Feagler | Illustrations by Jeff Suntala

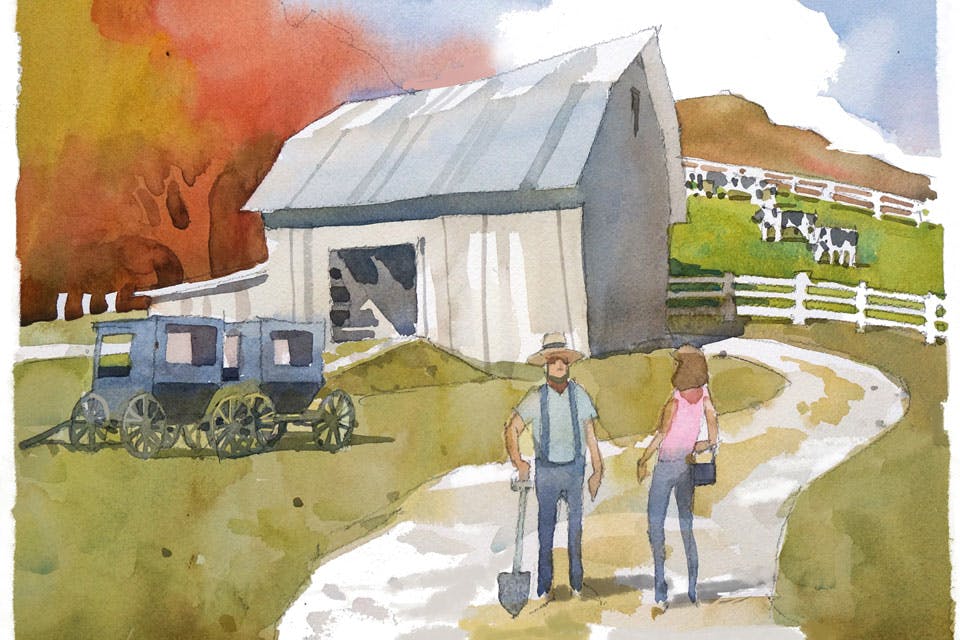

On the Farm

David Miller Jr.’s tours offer a firsthand look at an Amish dairy farm and a 45-minute buggy ride over the rolling hills.

Although the sun has yet to peek over the horizon in Tuscarawas County, David Miller Jr.’s day is two hours old. After rising at 3:30 a.m., the 56-year-old Sugarcreek farmer shepherds his herd of 40 Holstein cows into the barn and milks them with help from his 17-year-old son, Nathan, and 20-year-old daughter, Amy.

After a 6:30 a.m. breakfast of cereal, eggs and toast with his wife, Sharon Sue, and their six children, Miller heads back outdoors. It’s time to feed the 22,000 chickens he’s raising for a local poultry company and plow the alfalfa, hay and timothy fields with the help of six draft horses. The crops will be used to feed the Millers’ livestock during the coming winter.

“I could do an easier job with less work, leaving home at 5 or 6 and returning at 3 or 4 and have more idle time,” he says. “But I enjoy farming, and it’s a nice place to raise a family.

“We take the Bible real seriously: Our first parents were in the Garden and there was vegetation there,” Miller adds. “Don’t get me wrong. I’m not an earth worshipper or a tree hugger or anything like that. But you get a thrill out of working with the soil and watching things grow and do well.”

It is why the farmer extends a warm welcome to visitors eager to learn more about his way of life. Miller leads them on a tour that includes a stop in the dairy barn; a meet-and-greet with Vicky, a Dutch harness Standardbred cross horse who adores being petted on the nose; and a stroll through Sharon Sue’s garden, a colorful oasis of hydrangeas, petunias and roses.

One of the most appealing attractions is the chance to leisurely clip-clop along Pleasant Valley Road for 45 minutes with Miller in one of the family’s wood-and-vinyl buggies.

“People are fascinated by our transportation,” says Miller, as he prepares for a ride by hitching Tom — a docile 12-year-old Standardbred who spent his former life harness racing — to one of the closed vehicles he owns. “I often thought sitting behind a steering wheel … would appeal to me in a lot of ways.

“But if I look at the whole picture, I think I’d lose more than I’d gain. We don’t think cars are evil. ... However, we don’t think they’re family-friendly. … A horse and buggy helps us take life at a slower pace.”

Tom’s steady, 10-mile-an-hour trotting gait, coupled with a gentle breeze wafting in through the open windows can lull the uninitiated into a state of tranquility which begs the question: Why are we English folks (how the Amish refer to us) in such a hurry. Why aren’t we more often stopping to savor the moment? For Miller’s passengers, those glimpses of a simpler, slower life are filled with meadows of gently waving wheat and corn.

“There are so many distortions about [us] plain people,” Miller says. “I have a passion to share my faith with anybody. My ultimate goal is to get to heaven, and I’d like to see as many people there as possible.”

To arrange for a tour of the Miller farm and a buggy ride, contact Amish Heartland Tours at 330/893-3248, amishheartlandtours.com.

***

Sweet Stop

Lydia Troyer offers an array of tasty chocolates as well as a chance to make your own with her.

The irresistible aroma of milk chocolate greets visitors to Lydia Troyer’s kitchen. But, she explains, not just any kind of the sweet stuff will do. To create her delectable candies, the Millersburg resident uses Peter Superlative Chocolate, which she purchases in 10-pound slabs at Walnut Creek Foods.

“There’s no wax or paraffin in these bars,” Troyer says. “You can really see and taste the difference.”

It’s clear that Troyer, 59, has become a connoisseur of confection. That acumen began 50 years ago when, as a precocious 9-year-old, she began working at Troyer’s

Homemade Candies. Her mother, Anna, had launched the home-based business to supplement the income generated from the family’s dairy farm, which was just enough to feed the livestock, Troyer and her nine siblings.

“At first, I didn’t enjoy making candy much because I got tired of rolling the peanut butter and nut clusters that mom would dip into the melted chocolate,” she recalls. “And because I was a little girl, I would make [them] too big. Then, I’d have to start all over again.”

Business blossomed when the Holmes County resident and her sisters began selling homemade caramels and rocky road squares at the public school they attended in Millersburg. When Anna died in 2012, Lydia took the helm. These days, in addition to the 1,800 pounds of candy she produces each year, Troyer conducts make-your-own buckeye classes in the lower level of her home, which has been transformed into an expansive kitchen filled with double ovens and pantries for cooling chocolate.

“Who can resist chocolate and peanut butter?” she asks. “I enjoy talking with customers and helping them make something they can be proud to take home with them.”

The morning of a candy-making session, Troyer sets her gas oven on “warm” and places the chocolate inside so that it will melt to a consistency that’s soft but not scorched. To ensure a glossy, firm finish, she tempers it by heating it to 120 degrees Fahrenheit, cooling it to 82, then raising it back to 95.

By the time Troyer’s students arrive, sugar and sweet-cream butter have been added to the mixture that’s simmering on top of the stove in the same stainless steel bowl her mother used in 1960. Cookie-dough scoops in hand, visitors get to work rolling golf-ball-sized orbs of peanut butter and dipping them into individual bowls of chocolate. Each participant is presented with six pieces to take home as a souvenir.

Visitors can also browse the small on-site candy store, which is managed by Troyer’s sister, Esther, and stocked with perennial favorites that range from 10 varieties of truffles (including chocolate, coconut, lemon, orange and vanilla) to pretzels dipped in peanut butter to chocolate-covered Rice Krispies bites. Over the years, new kinds have been added, such as crunchy butter puffs made from Shearer’s Butter Corn Puffs, which have become Troyer’s favorite. Sugar-free varieties of best-sellers are also part of the mix.

“Years ago, I thought, ‘Hmm, do I really want this life?’ ” says Troyer. A member of the Old Order Amish, she explored the outside world in her youth by participating in rumspringa when she was 17. “But I always knew the answer would be ‘yes.’ My roots are here. My mother built this business, and the last thing I’d want would be for it to go away.”

To make candy with Lydia Troyer, contact Amish Heartland Tours at 330/893-3248, amishheartlandtours.com. Appointments can also be made via Country Coach Adventures at 877/359-5282, amishadventures.com.

***

Woven by Faith

Mattie Hershberger’s basket-making business offers a glimpse into one of the most conservative groups within Old Order Amish society.

Mattie Hershberger carefully considers each of the questions posed by inquisitive visitors who stop by her Dalton farm, located in rural Wayne County.

Is it difficult to not be allowed to ride in a car except in an emergency? How can you stand wearing that heavy clothing in the summer? Why do you live like this?

The answer to each is as simple as the long-sleeve, midnight blue dress and starched white cap Hershberger wears despite the sweltering summer heat: It’s tradition. “I understand why people ask,” she adds. “They didn’t grow up like this. But this is what we know. We prefer the old ways.”

Swartzentruber Amish is one of the most conservative subgroups within Old Order Amish society. Currently, there are 19 church districts in Wayne and Holmes counties, where the group originated. Because the Swartzentrubers eschew worldly signs, their easily recognizable buggies lack the orange triangle, reflective tape and other safety features that have been accepted by other Amish groups.

And, because the Swartzentrubers discourage interest in outward appearance, which members believe promotes vanity and pride, the Hershberger farm has a rough facade and lacks the colorful flowerbeds permitted in other groups.

Staid restrictions on use of technology also affect ways members can earn a living. For Hershberger, that made a sorrowful year even more difficult. Last summer, her husband Sam, a carpenter, was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He died three weeks later.

“It was hard,” Hershberger, 42, says quietly, admitting she worried about how she and her 10 children — ages 2 to 19 — would survive on their 68-acre farm. The answer was found in the family’s barn: She and Sam had spent evenings there making wooden baskets to sell to sight-seeing groups. “People who visit us seem fascinated by the baskets and wonder how we make them,” she says.

So, earlier this year, Hershberger began offering the public the opportunity to visit the farm and craft breadbaskets.

She orders veneer strips from Pennsylvania in green, burgundy, black, red, blue and natural and enlists the aid of her 14-year-old son, Aaron, to help those who are all thumbs.

The amiable teen, who has just completed eighth grade — his final year of formal schooling — begins by dipping the 3-foot-long wooden strips into water to soften them. Next, he demonstrates how to wind the bands around a wooden block to achieve the proper form, create the interlacing pattern, pound the tiny nails that hold the shape and, finally, attach the leather handles. Each basket takes 45 minutes to complete.

“It can be a little tricky, especially around the corners,” he says. “I’m happy to help.”

To make an appointment, write Mattie Hershberger, 17223 Goudy Rd., Dalton 44618, and include your phone number. She will borrow her neighbor’s phone to call you. Groups can contact Country Coach Adventures at 877/359-5282, amishadventures.com.

***

Comforts of Home

Mary Miller shares her soap-making craft and offers her guests a deeper understanding of the Amish way of life.

Mary Miller meticulously measures six drops of concentrated fragrance and adds them to the creamy white liquid simmering on the gas camp stove in her basement.

Each evening, after the cow has been milked and the bread has been baked, Miller retreats to the work space next to her wringer washing machine and makes soap. She crafts around 1,000 bars a year, which are quickly snapped up by gift shops in Ohio and Michigan and by visitors to her home in Geauga County’s Huntsburg Township on word-of-mouth recommendations.

“I don’t use much of the soap myself,” she says with a laugh. “Because the demand for it is so high.”

Miller, 48, attributes her product’s popularity to the goat’s milk she uses as a base and the pinch of oatmeal she adds to many of her concoctions. “Goat’s milk is known for making your skin soft, and the oatmeal exfoliates,” she explains. “I don’t believe in using harsh chemicals.”

Miller’s foray into soap-making began 13 years ago when her husband was involved in an accident that left him with a broken back and partially paralyzed.

Money was tight for the Old Order Amish couple and their five children. On the advice of her sister, Miller decided to try her hand at the craft.

Today, she relishes sharing the process with visitors to her home who wish to learn it. She helps them stir the solid blocks of goat’s milk she orders from a wholesaler into a rich, liquid consistency and choose a scent of their choice — lily of the valley, sweet pea, chamomile, vanilla, spiced cranberry, gardenia, water lily, ginger-peach and the ever-popular lavender.

While the slabs melt, she helps guests experiment with aroma strengths and at times raids her daughter’s box of crayons for a snippet of wax that will achieve the hue they’re after. “Everything is guesswork, but it seems to work,” Miller says.

Clearly, she enjoys teaching the mechanics of her craft, especially when it comes to helping her visitors get in touch with their artistic sides.

“A customer asked me to create a wildflower scent for her,” Miller recalls. “I admit it was a bit too potent for me, but she was happy with it. It’s always interesting to discover what scents are preferred over others.”

Once completed, Miller pours the soap concoction into square molds and allows each to set for an hour. While the soap hardens, she congenially leads visitors on a tour of the house, pausing by the contemporary Whirlpool refrigerator in the kitchen to explain that, since electricity is not permitted in her faith, the motor and cord were removed and bags of ice are used instead to keep the contents cold.

A peek in the bathroom decorated in delicate shades of teal and white elicits surprises from visitors who expected something a bit plainer.

But the Old Order Amish way of life is exemplified in the pantry, with its uniform rows of Mason jars filled with tomato paste, applesauce and cherry and blueberry pie filling that Miller canned with the bounty from the family’s backyard.

“I admit that when I decided to open our home to strangers, it was a turning point in my life,” Miller says. “It was necessary to make ends meet. But everyone who has made soap with me has been respectful, trustworthy and enjoyable to be with. ... If I weren’t doing this, I would be [someone] who would creep away from people. This keeps me going.”

For more information about making soap with Mary Miller, leave a message for her at 440/636-9808.

Related Articles

5 Do-It-Yourself Destinations in Amish Country

The parts of our state that Ohio's Amish and Mennonite communities call home are infused with hard work and self-reliance. These destinations embody that do-it-yourself spirit. READ MORE >>

Fun for Kids in Ohio’s Amish Country

Bring the little ones to Amish Country this season to stock up on adorable photos and great memories with the help of these destinations that promise to capture kids’ attention. READ MORE >>

Amish-Made Furniture Inspired by Famous Paintings

Holmes County’s Homestead Furniture collaborates with The Met in New York City to create collector pieces shaped by works of art from the museum’s collection. READ MORE >>