Ohio Life

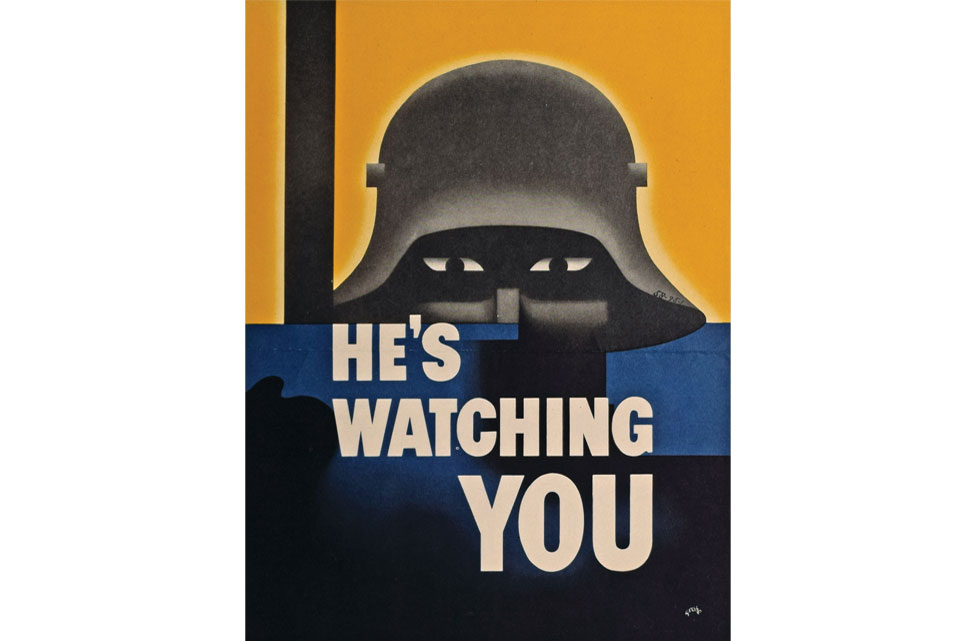

Call to Arms

The Dayton Art Institute showcases posters that rallied support in the lead-up to World War I and World War II.

Related Articles

See “Monet in Focus” at the Cleveland Museum of Art

This exhibition features five paintings by renowned French impressionist painter Claude Monet that show the various ways he captured light and atmosphere in his work. READ MORE >>

Visit the William Howard Taft National Historic Site in Cincinnati

Our 27th president spent his formative years at this hilltop residence in a neighborhood built for the city’s social elite. Today, the restored home shares his story. READ MORE >>

Visit the William McKinley National Memorial in Canton

Our nation's 25th president is honored with an ornate monument that serves as his final resting place. An adjacent museum tells the story of his presidency and Stark County. READ MORE >>